By Julian Bessinger

PAGA NANIA, Ghana— In the last decade, Ghana has been facing the challenges of a swiftly developing country. Forced to consider everything from wealth distribution from crude oil windfalls, to dealing with the plastic waste byproducts of a changing commercial system. The signs of these struggles are visible when you see a plastic bag in the surf at an otherwise beautiful beach, but also visible are the remains of the slave trade that characterized the colonial age.

Far north of the bustling capital of Accra rests the Pikworo Slave Camp. Established in 1704, and lasting all the way until 1845, Pikworo served as a slave collection outpost by Ghanaian traders who sold humans to the French, the English, and the Dutch. “An average of 200 slaves were here at any given time,” said James Suran-Era, an experienced guide. These slaves would be housed until it was time to transport them to the Southern Coast for transatlantic sale. “This journey could take two to three months,” said Suran-Era, “All on foot with no footwear, almost naked. Perhaps covered by leaves, or some animal skin for the men. The slave masters rode on horses.”

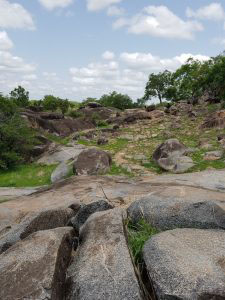

The camp itself leaves little evidence of its history at first glance, but guided by a knowledgeable eye, the past becomes more clear. There are glimpses of wide open field views, but look anywhere and your view is sure to be impeded by a rock formation, or a boulder that looks as though it has paused mid tumble. Atop a cluster of boulders there is a gash in one of the largest stones where the slave masters used to draw water. Around it there is a kind of field of manmade scoops in the rock. These scoops are bowls cut out by slaves who tried to escape, and were chased down.

This practice didn’t stop until it ceased to be profitable. Suran-Era has contempt in his voice when he speaks of the slavers last days. “Once slavery was abolished in Europe, people immediately ran away. They knew what was in store for them.”