The stories poured in over steaming bowls. People who had been forced to leave their countries were sharing their lives with New Yorkers, all while sharing the dishes from their homes.

The Refugee Food and Arts Festival in New York City brought locals together with refugees for a weekend in mid-September. By forming a community, they sought to raise awareness and find empowerment.

The event featured Syrian brunch on Saturday. In Midtown, Manhattan, people gathered in the FEDCAP building, a nonprofit dedicated to providing opportunities for economic independence, according to senior manager, Will Collins.

Pioneering the actual event, however, was Komeeda, a New York-based gastronomy organization. The festival was part of their ongoing “Displaced Kitchens” series, a campaign started earlier this year aiming to bridge the gap between refugees and their communities. Tickets ranged from $20 to $70, the proceeds helping refugees resettle in New York.

“Kitchens are also refugee camps,” said the creator of the “Displaced Kitchens” series, Nas Jab. “They accept anyone regardless of status; anyone can be in them.”

Sure enough, in the kitchen, chefs of various backgrounds were huddled around their stations. And as the Syrian brunch began, Venezuelan cooks were already preparing for a later meal. But this message of inclusion coursed through the entire event, even outside the kitchen.

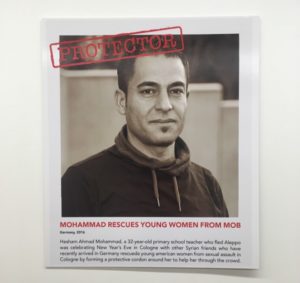

Artwork lined the walls, photographs of refugees in moments of heroism, with the word “protector” stamped across the picture in red capital letters. Trifolds stood scattered across the room, each with information on a different impoverished country and their food.

Back in the dining room this message rang true, three long tables taking up most of the space. For a few dozen people from around the city, this was an intimate setting. They were all chatting lightheartedly, making room for others, and making sure everyone received their fill. People passed the food around: fettah, foul madamas, and babaghanoush. But the star of the breakfast was served later: kufta (ground beef) and eggs, a dish which, upon tasting, one man immediately rose to compliment the chef.

The chef of brunch was named Ameenah, a Syrian refugee. She told her story in parts, unpacking her memories before a silent, tearful room.

She remembered her brother, who went to the store for bread and never came home (but who everyone later found out was alive). She said how the military police would shoot people at checkpoints because of their ID number, which secretly signified their religious sect. She showed everyone a scar on her forearm, from when the government whipped her while trying to take her son away.

Ameenah, who now caters from home, came to America this past Election Day. She faced the one of the challenges many refugees face: finding work when you are “unskilled.” The organizations Komeeda recruited tackle this issue. “We want to give them meaningful employment within the food industry by using their skills,” said Laura Miller, a member of one of these organizations, called Sanctuary Kitchen.

Last year, 85,000 refugees settled in America, 5,000 of them in New York. And while polls show a majority of Americans believe the U.S. isn’t obligated to accept refugees from places like Syria, organizations like Komeeda are devoted to providing sanctuary for these people. The goal is to help them develop their skills so they can make an impact on their community and make a living for themselves and their families.