A Mother’s Struggle With Addiction

by Stella Levantesi

Brooke August opened her eyes and found herself disoriented in the back seat of her silver Nissan Altima, parked crookedly on the side of a street in Newburgh, New York, an hour north of the George Washington Bridge. The car doors were flung open, her heroin doses were gone and her two-year-old daughter, Lily, was strapped in the car seat beside her, hitting her to catch her attention. “Mama, mama!”

August said she was high on heroin, and couldn’t remember what happened. The last thing she knew was that she had sat in her car, and driven off on one of her drug runs, raindrops falling on her windshield.

She was driving high on 3 bags of heroin with her daughter and a lady she met on the street, who had hooked her up with 10 bags of heroin to snort for $70 – a bargain considering she was used to paying 100$ for them. The stranger lady would get 3 bags for herself: that was the deal. When August woke up she knew the lady had run off with the rest of her doses as well.

“The only thing I remember after that was her [the lady] saying, ‘Pull over, you got the baby in the car and you’re nodding off at the wheel and you’re swerving on and off the road!’ I remember her vaguely saying something like this and the next thing I remember after that was that my car was parked, all the doors were open, and I was in the back seat, not even in the driver’s seat,” said August, her brown eyes widening as she recalled the scene.

It was April 2015 when, after this incident, the Administration for Children’s Services (ACS) requested a drug test for August. ACS placed Lily under the custody of her grandmother.

After the birth of her first daughter, August had been living with her father. “I had different cars there [at her father’s place], I’d be coming in and out all hours of the night, with my daughter, without my daughter, leave my daughter places – he didn’t notice anything,” said August. “My mom would never stand for any of that. She’d say to him, ‘You don’t see your daughter getting high?’”

“I don’t know if I overdosed, but I know I was definitely very out of it and even when I got home hours later my dad was like, ‘You looked fucked up’”

But after that rainy afternoon in Newburgh her father knew something was wrong. “I don’t know if I overdosed, but I know I was definitely very out of it and even when I got home hours later my dad was like, ‘You looked fucked up,’ and my dad never ever said that to me,” August said.

In the struggle with her addiction to opioids, August lost custody of her second daughter, Addy, as well. In 2016, when she was born she tested positive for marijuana.

This time ACS didn’t send Addy to live with her grandmother. They sent her to foster care.

Photo by Stella Levantesi

Like August, an increasing number of women have had to face similar issues because of their opioid use disorder.

* * *

In 2017, there were 1,646 pregnant women admitted to treatment programs certified by the Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services in New York State (OASAS). These numbers only reflect the women who were admitted for treatment, not the total number of pregnant women and mothers with opiate use disorder.

Half of the women admitted to treatment programs in New York, listed opioids as a primary substance disorder. And August is one of them.

After having spent 16 months at Samaritan Daytop Village, a residential program in the Bronx, which she left in November 2017, she was admitted to treatment at the Center for Comprehensive Health Practice (CCHP), located within Metropolitan Hospital in East Harlem, New York.

CCHP is an outpatient clinic where pregnant women and mothers enrolled in a program called PAAM, Pregnant Addicts and Addicted Mothers, tailored to meet the specific needs of pregnant women struggling with opiate addiction or mothers who have used during pregnancy and already had their baby.

According to the Center of Disease and Prevention (CDC), the rate of opioid use among pregnant women has quadrupled over 15 years, increasing from 1.6 per 1,000 women in 1999 to 4.9 per 1,000 women in 2014 and keeps on growing.

Dr. Hillary Kunins, Assistant Commissioner at New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, said the increase mirrors the rates of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) – which makes the baby dependent on opioids, and is often treated with medications like morphine because there’s a physical tolerance to the medication in the baby after birth.

“One really important thing is that we don’t use the word addiction [for] babies because [addiction] is a behaviorally based problem and all of that means is that there’s some physiologic dependence on a particular substance, and when that substance is withdrawn the baby might experience physical symptoms of withdrawal, agitation, irritability and so forth,” said Kunins.

Symptoms of physiologic dependance of the baby on opiates include excessive crying, fever, irritability, seizures, slow weight gain, tremors, diarrhea, vomiting, and possibly, death, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Kunin said that whether or not the mom has been prescribed opioids or taken an illicit opioid doesn’t matter to the baby, as it absorbs the substance like the mother does.

Photo by Stella Levantesi

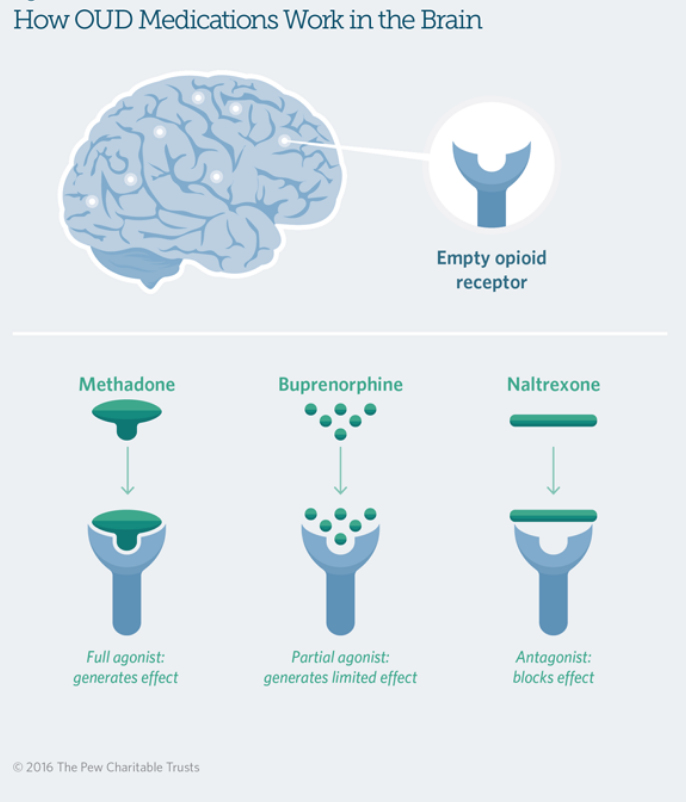

Opiates work on certain receptors in the brain and the body so when you suddenly stop using the substance, those receptors will be “hungry for the substance,” said Dr. Shabnam Shakibaie Smith who treats pregnant women with opiate use disorder at Columbia University Medical Center in Washington Heights, in northern Manhattan. “The correct assumption is that also the fetus has been exposed to the substance, so we can’t suddenly remove the substance without providing substitution, we have medication that we use so the [users] don’t go through physiological withdrawal.”

Medication-assisted treatment for pregnant women with substance use disorder is also recommended by the American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists. The so-called “opioid replacement therapies” include medications such as methadone or buprenorphine, and have the goal of avoiding acute withdrawal to mothers with opioid use disorder. These treatments help patients to reach a stabilized physical condition, allowing them to access rehabilitation.

“You’re substituting one addiction with another and people don’t realize how necessary that can be. The assumption is just ‘stop using, you’re pregnant.’”

But if methadone doesn’t replace opiate addiction in a pregnant woman, and the patient simply stops using, this could cause miscarriage and death of the baby in later stages of pregnancy because of acute withdrawal on the fetus.

August is being treated with methadone at CCHP, which offers a Methadone Maintenance Treatment Program (MMTP), designed, in part, for pregnant women who would suffer from dangerous withdrawal symptoms and risk losing the baby if they were to stop using abruptly.

Methadone and buprenorphine work differently on the receptor system. “With buprenorphine it could be tricky, if there is heroin or opiates in the system and you give buprenorphine [to the patient] then you would go through withdrawal because buprenorphine kicks them out of the receptor and sits there, but if opiates have left your system it sits on the receptor and then people feel better,” said Dr. Shakibaie Smith.

This means timing is crucial when prescribing buprenorphine. “The way methadone works is that it sits on opiate receptors and activates them so then you don’t go through withdrawal.”

Doctor Mariely Fernandez, chief medical officer at CCHP, emphasizes that social stigma against mothers with opiate use disorder doesn’t only affect the general public but even some medical professionals within the field. She said there’s a lot of physicians out there who still have a problem treating mothers and pregnant women who have a substance use issue.

The stigma tied to methadone extends to pregnant women and mothers with opiate use disorder.

According to Dr. Shakibaie Smith, the number of women using is increasing, especially in younger age, but the number of women coming in for treatment is still less compared to men. “During pregnancy women just refuse to come for treatment and reasons for that would be shame, fear of losing their baby, social stigma,” she said. “It’s something they don’t want to acknowledge because they’re very uncomfortable about it. They are aware of the stigma, because they probably have their own judgment against themselves and that is a major barrier to them in seeking treatment.”

August went through the social stigma herself. “In the beginning it’s hard and you’re trying to open up and people are judging you,” she said. “I didn’t want to open up for a while, I would only talk at CCHP.”

Fernandez said if users are seeking care and they’re getting the help they need you should commend them for that. “Nobody wakes up in the morning and says ‘today I wanna be a substance user.’ It’s things in life that happen that get you to a certain point, and we kind of have to be there when they come for help, it’s wrong to just turn your back and say, ‘shame on you for doing that,’” said Dr. Fernandez.

“What we know about being exposed to adverse traumatic events is they will have problems in the future with health and problems with mental health which then they can transmit to their kids: sexual and physical abuse, witnessing violence, parent incarceration, not having food in their homes [are all signs of trauma],” said PAAM program manager Liliana Villar-Durrani. Through an assessment of their patients called ACE they found that around 75 percent to 80 percent of women have at least one or two signs of exposure to adverse traumatic events.

“There were a lot of times where I felt, ‘I don’t want to do this anymore,’ and then I would get clean for a little while and then I’d go through something that was difficult and then I would want to use again,” August said.

* * *

August had been in jail for four months when she was pregnant with her first child Lily. Then a second time, while she was pregnant, for a month and a half. She was charged with possession of drugs and intent to sell, even though, she said, she wasn’t selling anything. “They laughed at me, they laughed at me when I told them it was personal use,” said August. “I was like ‘this is all mine.’”

When she got out of jail, however, August said she was clean and living with her mother who was keeping an eye on her drug use. After being clean for 11 months August said she relapsed. “I started using worse than I ever did before. I shot up a few times in the past before that, but this time, you know, that was all I was doing,” she said.

Initially, August said, she relapsed because taking out her wisdom teeth caused her pain, and she was prescribed painkillers.

“You can’t feel opioids [on suboxone], and I think that’s how a lot of people OD and die”

After relapsing August chose to go on suboxone, which contains buprenorphine and naloxone, a substance which treats narcotic overdose. Suboxone blocks out the opioids, so getting high takes a larger amount of opioids. “You can’t feel opioids [on suboxone], and I think that’s how a lot of people OD and die cause I guess they think they don’t feel it and they keep taking more and more and more and the body gives up,” said August.

But suboxone only worked briefly because she chose to stop taking it so she could get high again.

On Valentine’s Day three years ago, August said, Addy and Lily’s father strangled her. “He broke my glasses, broke the rearview mirror in my car, he accused me of taking his weed, which I didn’t do and it was a lot. I had a popped blood vessel in my neck, I had a lot of bruising, on my face bruises, on my arms, marks on my neck,” she said.

She relapsed again when she got pregnant with another baby from Lily’s father. August said he wanted nothing to do with it and told her to get an abortion. Although she said she was conflicted, August went through with the abortion.

“I ended up doing the abortion and it was more than just physical, obviously it was emotional, I went through a lot of shit with that,” said August.

“I was using everything. Everything,” she said, referring to the type of drugs she was on. “I used to steal a lot of stuff and sell it [to get money for drugs.] Pawn it. My uncle was living there [in her father’s house] before me, in the room I was in and he had left a bunch of stuff and I don’t know why it was like video games, jewelry, systems, stereos, all kinds of stuff so I sold all that and it helped for a little bit, not long, but it was something,” said August. She didn’t feel comfortable talking about the extent she had to go to obtain the money for her drugs.

August’s says her behavior has changed a lot since she got clean three years ago. “I always use to attack people ‘cause I always used to think I was being attacked, basically I was on the defense,” she said. “I was nervous about everything. Everything I said could be used against me, so it took a while.”

Fernandez said patients eventually develop trust and rapport with doctors, counselors and nurses, and you can see the change because they feel like it’s safe and they’re not judged, “they’re not treated like they’re treated outside of these walls.”

Photo Stella Levantesi

“In the 70s it was one of the first [resources for pregnant women and mothers with opioid use disorder] in the country, and still in New York there’s not that many doing it,” said Gadot. “We introduced this idea of integrating primary care with substance treatment so we offer pediatric care, free child care services, HIV treatment, diabetes, and other counseling services [all together if necessary.]”

And now CCHP also does overdose prevention. CCHP’s overdose prevention program was born in May 2017 and Gadot, who is also director of this program, said they go out to street fairs, community meetings and other treatment centers as their goal is to get naloxone kits into the hands of as many people as possible as well as their own patients.

Training people to use the kits is fundamental, Villar-Durrani said, in particular training friends and family members of patients with opiate use disorder. It works as a safety plan in the case of overdose.

Many women with opiate use disorder may be reliant or dependent on another person to get their drugs, “and that person usually either puts them through prostitution, sort of like a trafficking, but usually that’s a partner, and I’ve seen it quite often in my patients, especially late in pregnancy there has been a male figure that had them have sex with other men for money and that’s how they would provide for their lives,” Shakibaie Smith said. “Independence of these women is quite important and it helps in my experience when women have a support system.”

Although now the city is investing in overdose prevention programs, both Fernandez and Shakibaie Smith agree there is still a lack of resources for pregnant women and mothers with opiate use disorder.

“There are few places that are designed, residential places for women with opiate use disorder that help them to get their methadone and OB care. We need a lot more intensive, comprehensive treatment to be successful,” said Shakibaie Smith.

Sometimes, however, pregnant women don’t look for help. What often keeps mothers and pregnant women from seeking care is concern for custody of the child. This means that in most cases pregnant women are forced to choose between actively seeking help and rehabilitation, and avoiding criminal charges for abuse and neglect of their child, which could in turn lead them to losing custody of their baby.

Photo by Stella Levantesi

In many states, women’s substance use during pregnancy is considered a crime. Dr Shakibaie Smith said, “One of the main problems is that in so many states [pregnant women using] is considered a legal matter rather than a medical matter.”

According to state law, at least 23 states including New York consider substance use during pregnancy child abuse, and 3 consider it grounds for civil charges. Law enforcement cracks down on prenatal substance use through a variety of criminal and civil laws, so that prenatal drug exposure can provide grounds for withdrawing custody of the child and parental rights because of child abuse or neglect.

According to the Guttmacher Institute for Population Research and Dissemination, 24 states and the District of Columbia require medical professionals to report suspected prenatal drug use, and 8 states require them to test for prenatal drug exposure if they suspect any drug use.

Although New York isn’t one of these states, in many cases, mothers with opiate use disorder still end up in jail, and sometimes, like in Brooke’s case, during pregnancy.

Access to drugs is important, said Shakibaie Smith, and partly explains the opioid epidemic: An increasing number of people had access to opiates, creating higher exposure in the long-term.

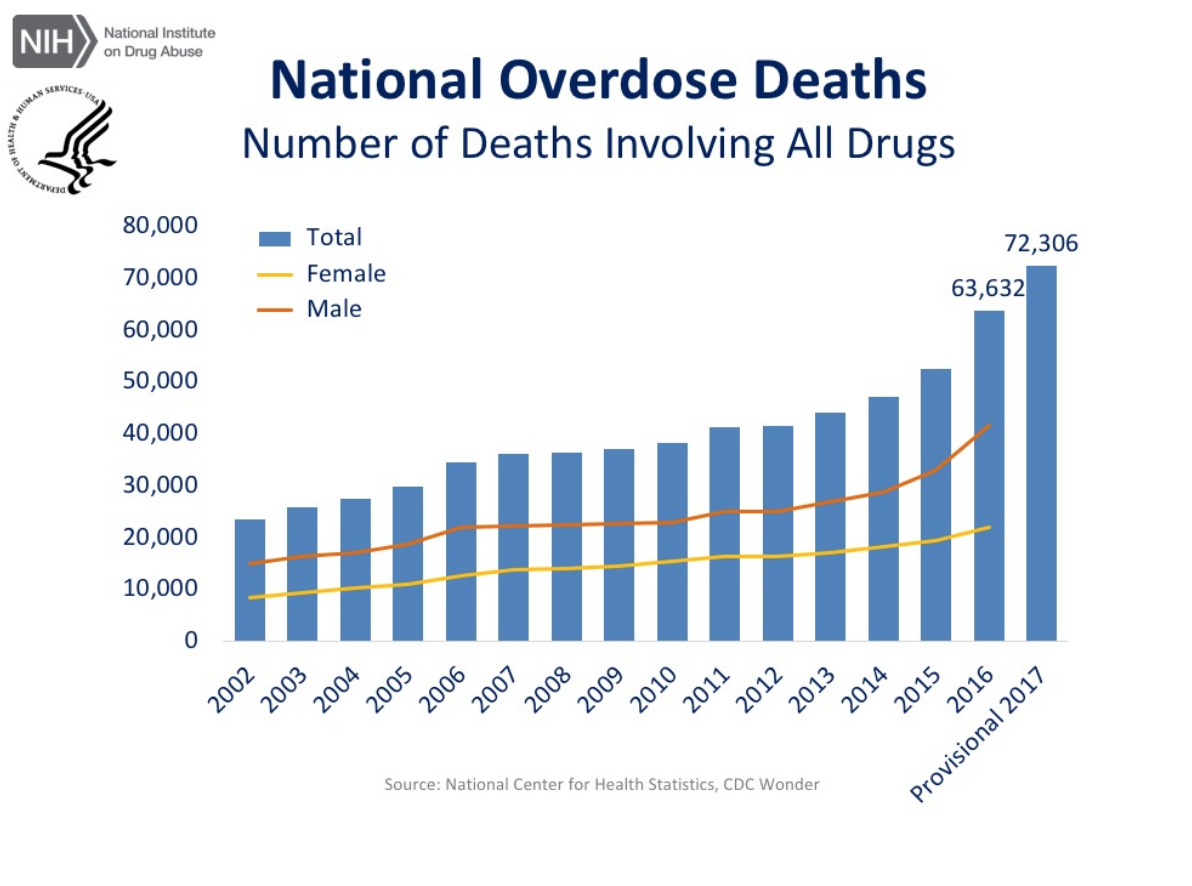

From the early 2000s there has been an increase in deaths by overdose, but in 2012 there was a dip because, Gadot said, there were no prescriptions for opiates going out so people started going to the streets. That’s when the epidemic broke out with heroin use and the trajectory becomes a peak. Around the end of 2014 and 2015, especially in NYC, use of opiates skyrockets because of the appearance of fentanyl on the streets and in medications. Fentanyl is a drug around 80 or 100 times stronger than heroin and has caused the surge in deaths because it is also much cheaper than heroin and more easily accessible. “I think it took about a year for the city and state to realize what was going on and that’s why there’s so much money now about overdose, because it’s so high right now in the city,” said Gadot.

The current opioid crisis has caused a yearly surge in death by overdoses of both men and women. According to the Department of Health, last year the US lost more than 72,000 people to overdose, including a record high of 1500 deaths in New York City from opiods.

***

“There were a lot of times where I felt, ‘I don’t want to do this anymore’ and then I would get clean for a little while and then I’d go through something that was difficult and I would want to use again,” said August. “Then I would realize ‘Ok, now I lost friends, family members, my job, my apartment, my car, I lost everything, literally everything. And was in jail.”

“That still wasn’t a low point for me. I think lowest point would be losing my kids. For me that was like ‘I can’t, I don’t want to do this anymore,’”

But losing everything and going to jail wasn’t enough for August to stop using. “That still wasn’t a low point for me. I think lowest point would be losing my kids. For me that was like ‘I can’t, I don’t want to do this anymore,’” she said.

For Villar-Durrani, success in treatment doesn’t mean only being clean. “A patient might still be using but they are making steps towards dealing with an issue that maybe they weren’t even aware that they had,” she said. “Family relationships, not being incarcerated, going to the referrals, improving their behavior, coming to sessions, these are all improvements. So the rate of success isn’t only not using.”

Photo by Stella Levantesi

Today August lives in a shelter, Harlem Family Residence, with her two daughters of whom she obtained custody, and looks forward to having a job, as it’s her next step toward finding a home for her and her two daughters, but she said it’s hard to handle both of them on her own, and having a job will make it harder. But she says having drugs out of her life is her priority. “It’s not really living [when you’re using], you’re just spending every second of the every day trying to find ways to get more drugs,” August said.

The fear of having her daughters taken away permanently was a big wake up call for August. “If I’m not healthy I won’t be able to take care of them [her daughters], I tell ACS all the time, even though they don’t believe me,” she said. “[In the beginning, she thought] I’m gonna end up either dead or in jail.”

But August has come a long way. “I’m proud of myself, I’ve come a long way, and I tell my mom and she’s like ‘you’re still not doing shit’ and I’m like, ‘I’m clean’ and that’s a big thing for me because, honestly, I never thought I was ever gonna stop getting high.”

Photo by Stella Levantesi