The Opioid Crisis

by Sharon Choe & Clarrie Feinstein

“In New York City, every six hours, one person dies from an opioid overdose.”

—Kaitrin Roberts, Assistant District Attorney, Crime Strategies Unit, New York County District Attorney’s Office

What is the opioid crisis?

In the late 1990s, healthcare providers began to prescribe pain relievers at greater rates. For years, pharmaceutical companies assured the medical community patients would not become addicted to opioid pain relievers. But, the increased prescription of opioid medications led to a widespread misuse of both prescription and non-prescription opioids and proved to be a highly addictive drug.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services declared the opioid epidemic a public health emergency.

In the United States

130+ people die everyday from the opioid crisis

2.1 million people have an opioid use disorder

2 million people misused opioids for the first time

11.4 million people misuse prescription opioids

19,413 people died from synthetic opioids

17,087 people died from prescription opioids

886,000 people use heroin

81,000 people used heroin for the first time

15,469 deaths are attributed to heroin overdosing

72,306 drug overdose deaths

42,259 of drug overdoses related to opioids

In New York State & City

1.9 million New Yorkers have a substance abuse problem

Of this 1.9 million, 156,000 are children aged 12-17

31% spike of opioid prescriptions from 2008 – 2011

96,883 people enrolled in chemical dependency treatment programs each day in 2015

25% of all primary treatment admission in 2012 accounted for heroin use

6,800 people have died from a drug overdose since 2010

1,487 confirmed unintentional drug overdose deaths in 2017

There were 62 more deaths than 2016

The Opioid Crisis, Part 1: The Drugs & Antidote

On Opioids…

Opioids are pain-relieving drugs that work to interact with the opioid receptors in our cells. Opioids can be made from the poppy plant, which is where opium derives from, and is used to make morphine. Synthetic opioids are made from fentanyl. Fentanyl is 50 times more potent than heroin and 100 times more potent than morphine.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there are two types of fentanyl:

- Pharmaceutical fentanyl which is prescribed to manage severe pain, such as with cancer and end-of-life palliative care.

- Non-pharmaceutical fentanyl is referred to as illicitly manufactured fentanyl (IMF). IMF is often mixed with heroin and/or cocaine or pressed into counterfeit pills—with or without the user’s knowledge.

Infographic by Health and Human Services

Most Common Prescription Opioids

-

- Codeine (only available in generic form)

- Fentanyl (Actiq, Duragesic, Fentora, Abstral, Onsolis)

- Hydrocodone (Hysingla, Zohydro ER)

- Hydrocodone/acetaminophen (Lorcet, Lortab, Norco, Vicodin)

- Hydromorphone (Dilaudid, Exalgo)

- Meperidine (Demerol)

- Methadone (Dolophine, Methadose)

- Morphine (Kadian, MS Contin, Morphabond)

- Oxycodone (OxyContin, Oxaydo)

- Oxycodone and acetaminophen (Percocet, Roxicet)

Naxolone: The Antidote to Opioid Overdoses

Naloxone and overdose prevention kits. Photo by Alessandra Rincon.

According to the Harm Reduction Coalition Naloxone, also known as Narcan, is a “medication called an ‘opioid antagonist’ used to counter the effects of opioid overdose, for example morphine and heroin overdose.” Naloxone can be taken anytime and is a non-addictive substance, which only works when an individual has opioids in their system. It alleviates the drug users respiratory and cardiovascular systems allowing their heart rate and breathing to normalize.

Naloxone can be injected in the muscle, vein or under the skin or sprayed into the nose, making it easier for laypeople to use, so that friends, family and community members can all assist in preventing drug overdoses.

The Opioid Crisis, Part 2: Policy and Solutions

Drug Policy

New York City and by large, the United States, is experiencing a shift in drug policy practices. Drug use is still seen as a criminal act, but in order to combat the opioid crisis, which is killing people at an exponentially high rate, legislators, law enforcement and policy makers are trying a new approach; they want to make the opioid crisis a public health issue. But since the 1980s, activists and scientific research have pushed for public health solutions for the opioid epidemic. So, why are we seeing this shift now? And can it really make a difference?

History of drug laws in New York City

“The Rockefeller drug laws were devastating in this state and across the country and even around the world, because there were a lot of copycat laws made after this. They were highly draconian.”

—Policy Manager Mike Selick, Harm Reduction Coalition

Photo by Stella Levantesi

In the 1960s and 1970s New York state was facing an insurmountable problem – the drug epidemic. New York City was in the midst of a heroin crisis. At the time, Republican Governor, Nelson Rockefeller, saw the issues as a social problem, backing drug rehabilitation and more preventative action. He created the Narcotic Addiction and Control Commission in 1967, aimed at helping addicts get clean, but it proved too costly.

In 1973 calls for harsher drug laws grew, enacting some of the most severe drug laws in the country’s history. Rockefeller enacted the Rockefeller Drug Laws, which created mandatory minimum sentences of 15 years to life for drug dealers and addicts. This included possession of small amounts (as little as two ounces) of marijuana, cocaine and heroin.

The Rockefeller Drug Laws sailed through New York legislation and the rest of the nation quickly caught on to New York’s “tough on crime” approach, fully fueling Nixon’s war on drugs.

Finally, in 2009, the New York Penal Law and the New York Criminal Procedure Law removed the mandatory minimum sentences. Judges now have the authority to sentences guilty parties to shorter sentences, probation or drug treatment programs. That year the New York Governor David Paterson stated, “I can’t think of a criminal justice strategy that has been more unsuccessful than the Rockefeller drug laws.”

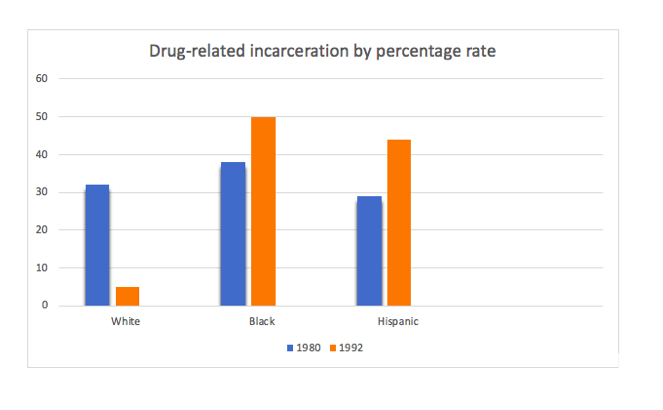

The consequences of the drug laws have disproportionately hurt communities of color, creating long-lasting impacts on the general well being of these communities. According to the ACLU in 1980, 886 people were incarcerated for drug related offenses in NYC. Of these individuals 32% were white; 38% were black; and 29% were Latino. In 1992, the state’s highest report for drug offenses listed 5% white; 50% black; and 44% Latino.

“I always look at my community as one of the communities that was disproportionately affected by the Rockefeller Drug Law reforms. We lost an entire generation of people for low level drug offenses and high level drug offenses…people were put away for generations or decades.”

—Carmen de la Rosa, Assemblywoman (Washington Heights)

The Shift to Public Health

“I very much see the opioid crisis as a public health issue. It is a disease and one thing that prevents people from getting help is inadequate services. They end up being treated as a criminal, so there is a lot of stigma around addiction and that stigma keeps a lot of people hidden.”

—Awilda Torres, Outpatient Addiction Program Unit Director at Inwood Community Services

“Law enforcement are often the first responders to the scene, but this is a public health issue.”

—Assistant District Attorney, Kaitrin Roberts

What is being done now?

Drug Policy Alliance:

The Drug Policy Alliance (DPA) has been pushing for drug reform since the 1980s. With offices located in five states, one being New York, the DPA is furthering the decriminalization of drug laws in numerous ways.

by Farnoush Amiri

According to the DPA, drug criminalization would eliminate criminal penalties for:

- Drug use and possession

- Possession of equipment used to introduce drugs into the human body, such as syringes

- Low-level drug sales

Removing criminal penalties for drug possession and low-level sales would:

- Save money by reducing prison and especially jail costs and population size

- Free up law enforcement resources

- Prioritize health and safety over punishment for people who use drugs

- Reduce the stigma associated with drug use so they can seek the support and treatment they need

- Remove barriers to evidence-based harm reduction practices such as drug checking, heroin-assisted treatment and medical marijuana

Harm Reduction Coalition:

‘People say the work that we’re doing is enabling. The only thing we’re enabling is for people to look after their health.”

—Mike Selick, Harm Reduction Coalition

The Harm Reduction Coalition (HRC) aims to reduce the barriers in place that stop people with drug use disorder receiving the medical treatment they need. HRC wants to expand syringe access, overdose prevention, access to healthcare and destigmatizing marginalized communities.

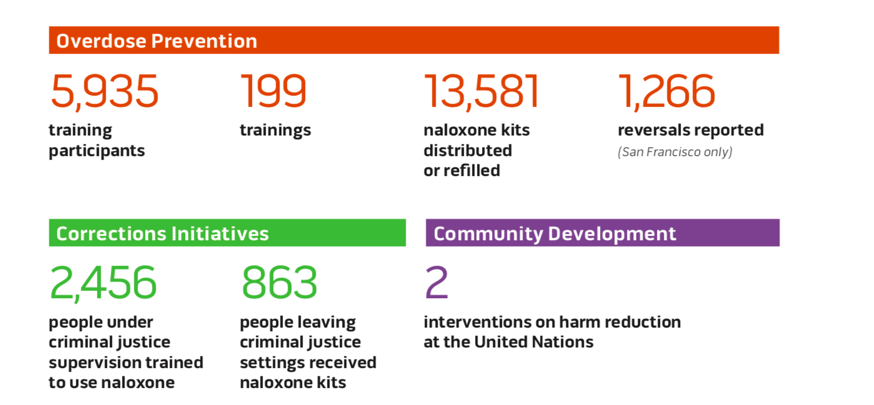

Achievements of the Harm Reduction Coalition in 2017 according to their annual report.

New Solutions

“SIS provides a safe place, where people feel accepted. It improves their quality of life.”

—Assistant District Attorney, Kaitrin Roberts

Since the 1980s the mission for harm reduction has been to reduce the harm associated with psychoactive drugs in people unable or unwilling to stop. Through policies, programs and community practices harm reduction focuses on preventing harm, rather than preventing drug use itself and individuals who continue to use drugs. Access to treatment is essential for individuals with drug problems, but many are unable to get the treatment needed.

Photo by Alessandra Rincon

Supervised Injection Sites (SIS)

Photo by Stella Levantesi

SIS is a form of harm reduction, umbrella term used in public health to describe a “philosophy that emphasizes lessening the harms of drug use.” By whatever name they are called, the sites are one of the harm reduction methods gaining momentum in the modern era of dealing with the opioid crisis as a public health issue.

In its function, supervised injection sites are service stations where ideally users would consume their drugs in a safe space, with clean tools and a trained staff standing by to provide first aid care and emergency, life-saving treatment in cases of overdose.

The Drug Policy Alliance outlines the various names for these sites: supervised injection sites (SIS), overdose prevention centers, safe or supervised injection facilities (SIFs) or drug consumption rooms (DCRs). These all fall under the broader scope of supervised consumption services outlined by the Drug Policy Alliance.

Currently, there are over 100 SIS in the world. They are predominantly found in Europe, Australia and Canada. The latter pioneered the approach in North America, wherein government sanctioned the first legal supervised injection site (i.e. In Site in Vancouver, CAN).

Their presence in the United States remains illegal and unsupported by the DOJ at this time—despite their operation in some of the nation’s more liberal cities, such as the SIS operated by the Corner Project in Washington Heights in New York City. The DA’s office does not oppose the treatment approach, but does not presently acknowledge the illegal operation of these sites in the city.

MEDICAL-ASSISTED TREATMENT

ADA Roberts speaking at an opioid forum in October. Photo courtesy of DA’s office.

The first responders to an opioid overdose are law enforcement. This may explain the old model of mass incarceration in regulating drug-related crimes. As the Manhattan DA’s office under Cyrus Vance Jr. began the shift to regarding the crisis as a public health concern, administering appropriate medical treatment to the victim now takes precedence to policing the drug crime.

ADA Kaitrin Roberts affirms that substance abuse is a medical disorder and their office advocates for patient-driven treatment. While not available nationwide, all New York City corrections provides medical-assisted treatment. The DA’s office began a partnership six years ago with the NYPD, fire department, city corrections and the public health sector to come up with creative solutions via mutual education and challenges. Roberts notes that this initiative preceded the 2016 spike in deaths and fentanyl overdoses. In addition to medical-assisted treatment for drug users, the DA’s office provides the Alternatives to Incarceration path.

GOOD SAMARITAN LAW

In 2017, 40 states and the District of Columbia passed the Good Samaritan Law, which provides protection from low-level drug offenses, like the sale or use of a controlled substance or paraphernalia, for a person seeking medical assistance as well as the person who overdosed. Oftentimes, the greatest barrier to seeking medical treatment from overdosing is interactions with law enforcement. In New York City, people can now call 911 without fear of arrest for witnessing or being part of a drug overdose.

Some limited states provide broader protections, including covering arrest, probation and parole violations. Vermont’s Good Samaritan law is the most expansive — it provides immunity for any drug-related offense, including drug sales.

Both the DPA and HRC have been instrumental in passing the Good Samaritan Law.