The two-story home perched on the edge of Irving Avenue offered no indication of what transpired behind closed doors. Picture frames filled with uplifting messages such as, You got this girl and A smile is the prettiest thing you can wear, dotted the white walls. Many women have faced the walls of this sobriety house in their battle against addiction. ‘Sammi’s Safe Haven,’ demands the greatest attention upon entry of the home with its peculiar placement over the living room door.

Two years ago, the Henehan family lost their daughter to an accidental heroin overdose. According to the Drug Enforcement Agency, 84 people died from accidental overdoses in Lackawanna County in 2016.

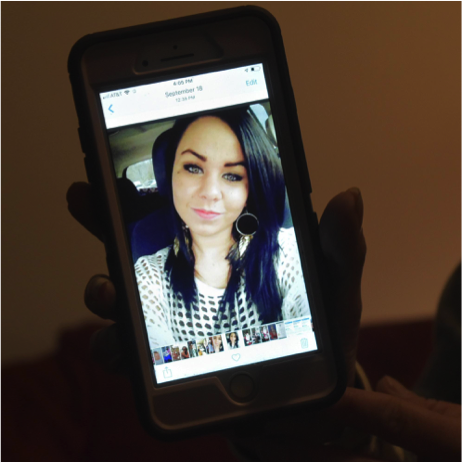

Samantha Henehan, 23, was one of them.

Samantha overdosed on April 10th 2016, only two months after Governor Tom Wolf’s declaration of a statewide opioid crisis.

“When she passed away it was like an atomic bomb had hit Scranton,” Stacy Henehan said as she choked back tears. Samantha’s mother said that her daughter was popular amongst those who struggled with addiction in the Scranton community. “Here she was as a professional finance banker at a Fortune 500 company, not a kid under a bridge,” Martin Henehan, Samantha’s father, said.

Martin’s face wrinkled in pain as he recalled his daughter. “The disease of addiction tells you that you don’t have it,” he said. Martin struggled with addiction in his own life. He knows the strife of remaining sober all too well. Samantha’s story of substance misuse stretched back to her early youth, which is credited to deeply rooted mental health issues, Martin said. At 15, Samantha witnessed the terror of a shooting at a house party in which one of her close friends was severely injured. Stacy described Samantha’s addiction as one that was gradual and that began with prescription medication misuse and excessive alcohol drinking. In the months prior to her death, Samantha’s mother shared that she had witnessed unusual behavior that lead her to believe that had her daughter had started using heroin.

Stacy and Martin founded Forever Sammi, the nickname Samantha was known by, a grassroots non-profit organization in honor of their late daughter in July 2016 shortly after Samantha’s death. They hope to educate the local community on the resources available to battle addiction. Most notably, the foundation manages three sober living facilities. “Marty channeled his grief through the foundation after we lost our girl,” Stacy said.

Currently, the Henehan’s manage two male-only sober homes, and one female-only home. The fees required to sponsor individuals that stay in the homes are raised through fundraiser events and education panels that are source community donations. Since its inception, “Sammi’s Safe Haven” has helped roughly 100 individuals struggling with addiction to reclaim their lives.

Martin and Stacy Henehan are members of the Lackawanna County Opioid Coalition Organization, an association that conducts ongoing education panels throughout the county with the aim of increasing awareness on the opioid crisis. The panels continue to trickle into the end of October as midterms loom over the people of Scranton. In less than a week, voters will determine if Governor Wolf will remain in office as he runs for re-election. “Tom Wolf has some good people in office,” Martin said, “I’m optimistic about the direction Wolf has taken to address the opioid crisis.”

Martin believes that there is a gap in the medical treatment for those who battle addiction due to the nature of the healthcare system. The majority of at-risk individuals do not have access to insurance policies that cover the fees for services provided by long-term facilities. After discharge from a hospital or a rehabilitation facility, individuals are especially at risk for relapse, due to a lack of housing and employment, according to Martin. The halfway houses aim to bridge the gap by providing shelter, food, and basic necessities to people who need additional support. The ages of the recovering addicts in the Henehan’s sober homes range from 18 to 56, and there’s no limit to how long anyone can stay. The longest a resident has stayed so far is six months.

In the month leading up to Samantha’s death, her parents had reported her substance misuse to the local police and had her incarcerated to protect her from using after failing to stay clean. Martin said it was the hardest decision he has ever had to make. Two days after Samantha was released from jail, Scranton police found her lifeless body in a motel room. A toxicology screen found heroin in her bloodstream. Martin said that he had been working with local authorities to place Samantha in a random drug screening program a day before she overdosed. “Samantha was such a strong member of the recovery community,” Martin said.

According to Stacy, Samantha was sober from the age of 17 to 21, prior to her overdose. Her father believes that her story brought a mass of awareness to the addiction problem in Scranton because during her periods of recovery she excelled so significantly that it gave hope to those she knew who struggled with addiction to find success in their own lives. Now he hopes her story will continue to help those struggling.

“I have goals that I am working towards, like getting back in school, getting my permit, going to court to get my daughter back,” said Koren Stuart, 23 who currently resides in the women’s sobriety house. Her living situation, she said, has provided her the stability necessary to work toward her goals.

Today, Martin Henehan receives more than 400 phone calls a day and emails from struggling addicts and concerned family members who are seeking help. “The collateral damage is the physical separation from Sammi,” Martin said, “but the collateral beauty is the response to her story.”

Email the Author, Malak Saleh at mns435@nyu.edu