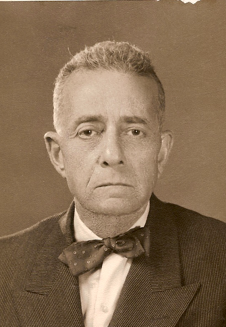

My great-grandfather was a lawyer from Cairo, Egypt’s bustling capital city. His father lost his shirt in the stock market with disastrous consequences, so when it was my great-grandfather’s turn to try his hand at making a fortune, he took a different tack.

In 1920, he figured the best investment was real estate. He constructed an apartment building in Heliopolis, a flourishing, quiet neighborhood in Cairo. He designed the building with the help of an architect and built the structure from the ground up. “A self-made man,” my mother calls him.

The structure is two small apartment buildings, side by side. The walls of one fuse into the walls of the other. Whenever I visited this building as a child, I was always amazed at the secret doors that passed from the pantry of one apartment to the hallway of the adjoining building. I suppose that’s what happens when families settle in Siamese-twin homes.

One of my great-grandfather’s first tenants was an Armenian named Kevork Hagopian, who arrived in Cairo in the 1930s. At the time, and for many years after, real estate “contracts” in Cairo were based on good faith and a firm handshake. That’s all my great grandfather required when Hagopian took up residence n the 2690 square foot, three-bedroom first-floor apartment — a New York Dream. Just one small gesture of trust: a handshake. In return, Hagopian promised to pay about seven Egyptian pounds a month in rent. That comes out to about one American dollar.

This was more than 70 years ago.

Hagopian was faithful to the handshake, even after he started going a little crazy. Hagopian wasn’t always crazy, though no one in my family can recall when Hagopian started to get a bit loopy. Maybe when he hit 60, around 1980. It’s hard to pinpoint a moment, but he was still paying his own rent in the ‘60s, so that was a good sign. He aged with the building. As the walls yellowed with time, he got older. He lived unmarried and alone. His social etiquette dried up like the sickly plants that lined his dying first- floor garden. It was always dark in Hagopian’s apartment. No one visited, no one came. He talked to no one except himself. As he got older, his nephew started to pay his rent.

Over the years, the outer walls of that building in Heliopolis have seen a lot: independence, three presidents, one massive nationalization plan, the assassination of one of those presidents, and a couple of wars, to name just a few. No wonder the walls have aged.

Charles, my great-grandfather, died in 1960. After his death, the Heliopolis property was split up and the various apartments passed down to his five children. He had four girls, and one boy. His only son, now the man of the family, dealt with the tenants and rents. One of the girls, Hilda, was my grandmother.

Inevitably, all five offspring had children of their own. Hilda, my grandmother, met my grandfather, a young lawyer of Armenian descent who worked in her father’s office. They got married and had two daughters, one of whom is my mother.

More offspring came. Bits and pieces of the building were passed down further. Ownership of the apartments was scattered across the globe, as the descendents moved to various places. Some stayed in Egypt and lived in the building. Others left. My mother married my father and moved away. Her sister, my aunt, ended up in France with her two sons. A few descendents remained to take care of the aging building.

Which brings us to the present.

Recently, my father’s foreign service job, which led to 23 years of country-hopping, led my parents back to a post in Cairo again, where they originally met. Suddenly we were re-immersed in the world of the Heliopolis building again. The many complications of its many tenants had exploded since its simple beginning in the 1920s. The storeowners on the first floor didn’t have contracts. The fifth floor tenant left her faucet on, causing an impromptu flood of water that poured down on the apartment below. The list of grievances grew longer and longer.

Pages: 1 2