Pelaez said there was a courtyard in the tourist district where teen and preteen boys and girls waited for European tourists to come take them into nearby hotels. Without enough money for a family to eat, these children are often turned to the streets.

“You see these kids and you want to put them [in front of] an Xbox [game],” Pelaez said. “I’m sure if I met five little girls on the block, at least three of them have [become prostitutes]. That’s the reality of life over there.”

One of Pelaez’s characters, Nikita, is based on this sad selling of childhood. Nikita was forced into prostitution by her mother to help take care of her sick grandmother. Pelaez performed Nikita’s monologue this year before New York University’s Cuban American Students Association. They watched silently as Pelaez stood at the front of a small room and became a 15-year-old girl, outraged at a tourist who slept with her, then offered to pay with half a Nestle Crunch bar. With a swing of her hip, and a push of her red lips, Pelaez captures Nikita’s fiery, rebellious nature as she threatens to hurt the tourist and tells him she’s seen what little bit of a man he is. When Nikita’s mom acquires visas to go to America, the little girl is tempted to give up, but in the end must stay in Cuba because her grandmother is unfit to travel. Nikita hopes the old woman will die while the old woman curses her for sinning. At last, the grandmother passes away…days after the visas have expired.

When performing this role, Pelaez said she remembers a dark-skinned little ballerina she encountered during one of her first visits.

“Mercedes…light as a feather, a skinny, beautiful girl,” Pelaez said. “[She is] incredibly emotional, never holding back.” “Hopefully she’s a dancer,” Pelaez said with a soft voice and distant eyes. But Pelaez knows this is unlikely. Racism is still very real in Cuba and because Mercedes’ skin is dark, her beauty and her talent will never reach the stage. “She must have grown up to be the most amazing little adult,” Pelaez said, almost like a wish. Though Pelaez revisits Cuba in her mind every time she performs her play, she has no plans to return to the island. Her great aunt has died, and although she still has friends and family she could stay with, the experience, she admitted, would be too much.

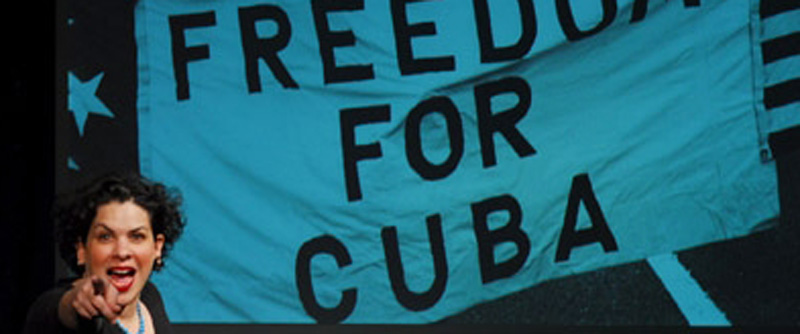

“I would be crying from the minute I wake up until ten minutes after I fall asleep,” Pelaez said. “Once there is a change of government, and there has to be, I will go back because I do want to rebuild that country. I would love to live in Cuba.” It’s that kind of passion for Cuba that carries Pelaez’s performance in the play. Although she’s willing to open it up and allow others to perform it, her close relationship to the subject and the characters allows her to “bring something special to it.” “It’s a very personal performance but I think the message is much more important than I am,” Pelaez said.

When she’s not performing the play, she misses it. The one person she’d like to have seen the play is her father, the man who inspired her and taught her who she is as a Cuban. He died when she was 13.

“Although, I kind of feel like he sees it,” Pelaez said. “I feel like mis muertos have been with me. I feel my dead have seen it because they’re so much a part of it.” Her mother and sister are big fans of the play and have been to see it many times. Pelaez said she thinks her family is proud about what she’s putting out to the world about their experience. Critics have agreed with the praise, the New York Times wrote the play was “Sweet & intoxicating… [a] richly embroidered show….As a writer, Peláez’s greatest gift is the specificity of character that she creates.” She won the 2008 Outstanding Solo Performance award from HOLA, the Hispanic Organization for Latin Actors.

The Cuba Pelaez knows is wrapped in the past and the present, much as it exists in reality. The dead, and the memory of days when the walls weren’t crumbling, float in the minds of Cubans until they’re almost tangible. To be Cuban is to live in the present, in the failed revolution and exile communities, and in the past, in the beautiful palms and the warm, colorful nights. “There is a Cuban shortbread cookie that when you put it into your mouth, it just crumbles,” Pelaez said. “When you put it in your mouth it just turns into sand. That’s what Cuba is like.”

2. Connecting

For a moment it was so quiet, they said, you could hear a pin drop. Three hundred Cuban-Americans sat in an auditorium at University of Miami with all eyes focused on one man. They were waiting to meet a man they’d only seen on a computer screen. They were waiting to hear the real voice of Cuban dissident.

As the air filled with anticipation, Kenneth Sinkovitz, a leader of Raices de Esperanza (Roots of Hope), introduced a man he had been longing to meet, ever since they connect a year ago via an underground video conference call. For the first time ,this independent Cuban journalist, whom Sinkovitz would not name out of concern for the man’s safety, met face to face with 300 of his U.S. supporters.

“You could just see he broke down in tears,” Sinkovitz said. “He was so touched by the magnitude of the people supporting him. He was actually seeing us all with his own eyes and hearing us with his own ears, rather than being filtered through a computer or phone.”