Ode to Joel Fabrikant

by Kim Deitch

He was a roughneck. He certainly wasn’t politically correct and his blunt management style definitely took getting used to. In fact I really didn’t know what to make of him at first. But during the time I worked at The East Village Other, I received any number of sanctimonious promises from the people I worked with that didn’t seem to amount to much. Joel Fabrikant was no sanctimonious hippie or any other kind of hippie, but he always kept his word.

I was actually drawing comics for EVO, as it was called by most of us, before Joel got there. The first time I showed up at the storefront office on Avenue A was at the start of 1967. Allen Katzman, EVO’s nominal editor, looked at the art samples I brought. He told me they were interesting, but that EVO was looking for work that was more, “psychedelic.” Psychedelic was a buzzword of the moment. Put simply it meant, “trippy,” or drug-influenced.

I didn’t have to go far to pipe directly into that. Before I even left the office, Allen Katzman introduced me to Bill Beckman, the art editor. I knew who Bill Beckman was. In fact he was one of my initial inspirations for showing up at EVO.

Back in Westchester, where I had been employed as a child care worker, perhaps nine months prior to this, I showed a co-worker some of the artwork I’d been doing in my spare time. A curious thing about this artwork was that at a certain point, it had started morphing into primitive comic strips.

First Issue

There were all kinds of reasons for this, but the key thing worth mentioning here was that as an art trend, comics were something that was in the air at the time. I didn’t fully realize how much so just yet, but I would soon find out over the next few years.

Anyway, while showing my co-worker my art, including some early attempts at comics, I told him I thought comics had real potential as a viable art form, but that the problem this made for me was that I really couldn’t draw all that well. In fact this stumbling block was also a key thing that attracted me to comics. There was a lot less room for b.s.-ing your way through as opposed to other trendy forms of artistic expression then prevalent.

He looked my comic pages over, paused, and said, “Gee I don’t know. The drawing is better than Captain High.” To explain, he showed me some recent issues of The East Village Other, where Captain High ran somewhat intermittently. It was all about a doper superhero, drawn by Bill Beckman. My co-worker had a point. I did feel that I was capable of competing with Captain High.

Bill Beckman looked over my samples and seemed to see promise. This led to work too, but not quite the kind of work I was expecting. However, within a day or two, I was making money, dealing pot for Bill Beckman.

I wasn’t a very good dope dealer. I was selling to my friends and naturally they wanted a good deal. Still, I was making some money and there was plenty of pot left over for me to smoke. So I smoked. I also kept on doing artwork and must have been psychedelically inspired. I came up with a comic strip about a chubby super-heroine called Sunshine Girl. Unlike Captain High, drugs were not part of its elemental storyline, but by God, it was psychedelic!

Kim Deitch

I took the first three episodes of Sunshine Girl back over to Allen Katzman and he seemed interested. He told me to wait, left me for a moment and returned with a good-looking, mustachioed guy with longish hair, who looked my strips over and got very enthusiastic. This was my first encounter with Walter Bowart, the man who was really running the show at EVO. He asked me if I thought I could get Sunshine Girl out on a regular basis. [I sure could!] And just like that, I was working for The East Village Other.

The downside was that there was no pay involved. But then again, I was dealing dope for the art director. So began my career as a published artist. I don’t say professional because the work wasn’t; and besides, professionals were paid money. Joel Fabrikant made me a professional, but that came later.

I initially met Joel late in 1967 when he came on board as EVO’s business manager, but he didn’t really make much of an impression on me at that time. By this time EVO had moved from its storefront on Avenue A to a loft up above the Village Theater at 105 Second Avenue, later the Fillmore East.

Things had begun to sour for me at EVO for a variety of reasons. I think my initial flush of success was, to some extent, beginner’s luck and by the end of the year I had decided to give it all up.

I took a civil service test and went to work at the Post Office. I also started going to Swami Satchidenanda’s ashram over in the West 80’s and rather magically, almost instantly got rid of most of my bad habits! I quit drinking, got more organized and started taking a night school art class at Pratt Institute where I had studied for two years in the early 1960s.

_comic.jpg)

Illustration by Kim Deitch

Over and above all that, I just generally became a happier, better-adjusted person. All I can say is, there must have been some powerful juju in the mantras they were making us chant at the ashram.

That was the situation when I had my first really significant encounter with Joel Fabrikant in the spring of 1968. Even though I was no longer doing comics at EVO the editors very kindly let me run a perpetual ad in the paper’s want ad section. The ad was for buttons that featured a picture of my character, Sunshine Girl, and a trickle of orders addressed to EVO were still showing up there. I’d come in every couple of weeks to pick them up.

Well one day in 1968, Joel Fabrikant spotted me and said, “I want to talk to you.” I couldn’t imagine what about as he ushered me into his office. Joel was a big beefy, hard-nosed kind of guy and had a rather thuggish aura. Picture Broderick Crawford in the movie “Born Yesterday.” He had a bullying manner. You didn’t really want to get on the wrong side of him. I’d seen him rough up more than one person who got out of line with him. But I also had the distinct feeling that they must have had it coming because, for all his surface crudeness, Joel had a pretty clearly defined sense of fair play.

So how did this guy end up running EVO? That is still something of a mystery to me. When I first faded from the scene, it was still Walter Bowart’s kingdom. I was aware, of course, that subsequently Walter had married a hippie heiress, Peggy Mellon Hitchcock, and quit the paper. But how Joel Fabrikant emerged as top dog is murky to me. He didn’t necessarily have the title. I’m not sure he had any kind of official title at EVO, but he sure as hell was running things and, at least from a business perspective, he was doing a good job.

I don’t know much about his background. Rumor had it that he came from money, but was now disowned by his family. Rumor also had it that he’d been offered a job as an accountant with the mob, but turned it down.

Illustration by Kim Deitch

Anyway, this is what he wanted from me that day. He wanted me to start doing comics for EVO again. Just before I left EVO the first time, Allen Katzman told me that Robert Crumb had dropped by and left a portfolio of stats of one-page comics. They were breathtakingly brilliant. For me, heartbreakingly so. I was outclassed and I knew it. It was one of the reasons that I got out of EVO, and comics.

When they finally used up all the Crumb strips they had, EVO’s circulation took a nosedive. I told Joel that I was perfectly happy with the way things now were and thanked him very much for the offer. But Joel Fabrikant wasn’t having it. He sent for Spain Rodriguez, who by then had the title of art director, but who was essentially doing comics and illustrations for the paper. I already knew him; a good guy if ever there was one.

Spain Rodriguez came in and Joel Fabrikant said, “Spain, don’t I pay you forty dollars cash every week, to do comics and illustrations?”

“Yeah, Man,” he laconically replied.

Joel Fabrikant looked me in the eye. The implication was clear enough. I too could be so blessed if I was smart enough to get with the program. He essentially felt that the key to getting back up to a strong circulation was to get more good comics back into the mix and no one seemed to know where R. Crumb was at that moment in time.

During this meeting, Joel Fabrikant told me quite frankly that he was in this situation strictly as a business proposition and that he didn’t even read The East Village Other. He certainly had no sympathy with new left politics. He was a staunch Republican. Go figure!

I was confused and fascinated. I couldn’t say I really liked Joel Fabrikant at first, but he sure as hell wasn’t boring. In fact he was, at least to me, very entertaining. And, insofar as my dealings with him went, I found him to be that rare thing in this imperfect world of ours, an honest man.

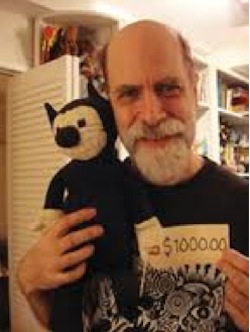

Waldo the Cat by Kim Deitch

In very short order, I too was making forty cash a week doing comics, illustrations and otherwise helping out at The East Village Other. Technically, I was now a working pro. In reality and more importantly, I was earning while I was learning. As far as I was concerned, it was the break of a lifetime; the greatest single thing that had ever happened to me up to that time and I owed it to Joel Fabrikant.

I won’t say that I ever really fully understood Joel, but I soon came to love the man. Over and above the salary we got, he really took care of us. He was 28 years old to my 24, but I thought of him as much older. Of course there was that violent streak of his. I do recall once having a rather heated argument with him. I forget what it was about, but his anger reached a point where I was thinking, “Is he gonna haul off and belt me?”

I knew well enough that he could have easily demolished me if things ever got to that point. Instead I held my ground, looked at him and carefully restated what I considered to be my side of things. Joel amped down and I can’t remember how the dispute ended. All I’m saying is, if you kept to civility and logic as you saw it, Joel was willing to give you a fair hearing.

Another thing to keep in mind is that in spite of all the so-called peace and love that the hippie movement proclaimed, the Lower East Side was a tough place. I think it always was. By this time I made it a significant part of my own security regimen to walk around with a loaded pistol in my jeans.

By 1969, a lot of things were changing. The real natives of the Lower East Side were becoming distinctly less tolerant of the hippie interlopers who were taking over their neighborhoods. And it was also becoming increasingly clear that the real future of underground comics was in San Francisco.

Joel Fabrikant with pie. Photograph by Joseph Stevens, from EVO’s March 3, 1970 issue.

Late in 1969 I relocated there with my girlfriend. I continued to receive complimentary copies of EVO every week in the mail. I guess they missed me because I noticed old doodles of mine and even abandoned comics pages sometimes turning up as illustrations. Unfinished strips of mine, finished by others, occasionally were published. I wasn’t paid for any of this and I suppose I could have made a fuss, but I chose not to do so. In actual fact I was more touched by this than anything else.

Around summertime in 1970, I heard the rather stunning news that Joel Fabrikant had quit the paper. Apparently Joel had summoned the entire staff for a rather blustery dressing down. In the midst of it, Robert Crumb stepped forward and shoved a whipped-cream “pie” in Joel’s face. Crumb, unlike me, was never especially charmed by Joel Fabrikant.

It must have crossed Joel’s mind to smack Crumb, but he didn’t. Nevertheless the incident affected him deeply and a few days later, he resigned. There is no man in the world I respect more than Robert Crumb, but I wish he hadn’t shoved that pie in Joel’s face.

Of course the EVO cover showing the incident is now the only picture of Joel I have and, as such, I treasure it. The undeniably comic look of apoplectic rage on Joel’s face; if I saw it once, I saw it hundreds of times.

Maybe he had it coming. I wasn’t there. God knows he had his faults, including that rather questionable management style. But like I said before, I loved that man and that can often cover a multitude of sins.

Dietch

I only saw him one more time. In 1972, I was back in New York for a trip and went with EVO’s last art director, Don Lewis, to visit him. It was great to see him again and he was so glad to see me. Unfortunately I had another engagement and couldn’t stay long. He was clearly disappointed and didn’t even try to hide it.

I never saw him again. A few years later I heard that he and his girlfriend died of an overdose of heroin. I have never really gotten over that. I don’t think he was much more than 40 years old. He may not have been living right, but his death really hit me hard. I owed him so much. As the years go by, I never pass up an opportunity to praise his memory. I guess he kind of knew I felt that way, but I still feel a terrible sadness when I think of him, which is often.

From Kim Deitch’s biography at Fantagraphics Books: “Kim Deitch has a reserved place at the first table of underground cartoonists. The son of UPA and Terrytoons animator Gene Deitch, Kim was born in 1944 and grew up around the animation business. He began doing comic strips for the East Village Other in 1967, introducing two of his more famous characters, Waldo the Cat and Uncle Ed, the India Rubber Man. In 1969 he succeeded Vaughn Bodé as editor of Gothic Blimp Works, The Other’s underground comics tabloid. During this period he married fellow cartoonist Trina Robbins and had a daughter, Casey. ‘The Mishkin Saga’ was named one of the Top 30 best English-language comics of the 20th Century by The Comics Journal, and the first issue of The Stuff of Dreams received the Eisner Award for Best Single Issue in 2003. Deitch remains a true cartoonists’ cartoonist, adored by his peers as much as anyone in the history of the medium.”