Peter Leggieri’s East Village Other

by Peter Leggieri

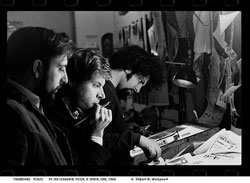

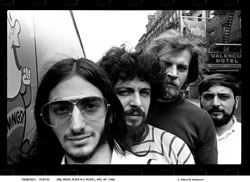

Left to right: Peter Leggieri, Peter Mikalajunas, and Spain Rodriguez

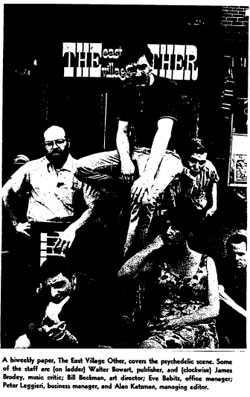

Earlier this week, the Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute launched “Blowing Minds: The East Village Other, the Rise of Underground Comix and the Alternative Press, 1965-72,” with a rousing discussion that’s now archived on the exhibit’s Website, along with new audio interviews with veterans of the Other. Over the course of seven weekend editions of The Local, we’ve heard from all but one of the EVO alumni who spoke on Tuesday’s panel. Here now, to cap off our special series, is the story of Peter Leggieri.

From the first day that I began working at The East Village Other, I was overcome by the sense that it was not only a newspaper but a strange and magical ship on a voyage with destiny. It seemed as though each issue printed was a new port of call, and the trip from one issue to the next, a new adventure. Many of EVO’s crew members expressed that same weird feeling – a sense of excitement and creative power.

And what a crew that was! No one was recruited. I don’t recall a resume ever being submitted. They all simply showed up and started working. EVO’s crew might just have been the greatest walk-on, pick-up team in the history of journalism. She was The Other but her staff of artists, poets, writers, photographers and musicians affectionately called her EVO. Her masthead bore a Mona Lisa eye. EVO created a cultural revolution and won the hearts and minds of a generation. She was the fastest ship in the Gutenberg Galaxy.

In the Beginning

I was the anonymous Other, the one editor-owner unknown to the public. I did not party. I did not schmooze with the literati or seek publicity. I had no time for such things. I worked seven days a week, 20 hours a day and, because of law school, I had to be sober. My friend, the poet John Godfrey, told me that I was afflicted with a Zen curse: a hermit condemned to be surrounded by people and events. That was certainly the case for me in the 1960s.

My life with The East Village Other began in the spring of 1966 when I lost a roommate, an unexpected event that threw my carefully calculated student’s budget completely off course. I needed about fifteen more bucks a week to survive. One Saturday, after a 39-cent breakfast at Leshko’s diner (two eggs, home fries, toast, coffee and fresh-squeezed orange juice), I noticed The Other’s small, ratty, roach-infested, slum storefront on Avenue A and decided to buy my first issue of the newspaper. Walter Bowart was behind the counter and we began to talk about newspapers.

Printers ink ran in my veins. I had begun my journalism career at the age of 13 as a three-silver-dollar-a-week stringer reporter of high school sports for the Troy Record, a daily in upstate New York. My association with newspapers had continued through high school and college (where I became a photographer and drew very bad editorial cartoons). I had also designed and written a glossy monthly newsletter when, as a college junior, I founded the first public relations department for the oldest hospital north of New York City, a 320-bed facility run by the Sisters of Charity, the “Flying Nuns.”

When Bowart heard that, he burst out laughing: “The Flying Nuns! Damn, you’d be perfect for us!” (I did not at the time understand what was so funny.) He was a tall, lean Oklahoman with blue eyes and a handlebar mustache. His spontaneous laughter was explosive and came with a cowboy’s chaps-slapping enthusiasm that could cause onlookers to take a reflexive step backward. (Gradually, as we became friends and collaborators, I would understand he was that rare person who always became visibly exited by ideas.) Bowart told me that he was looking for people with experience and that EVO desperately needed someone to manage advertising, even on a part-time basis. I told him I’d check my schedule and, a few days later, I took the job.

The Players

When I joined EVO, the little paper had published four monthly issues and four “fortnightly” issues. Amazingly, it had three editors :Walter Bowart, and Allen Katzman and John Wilcock.

Walter Bowart and Allen Katzman

Bowart was a painter who thought the way he painted: big broad strokes on a big canvas. He was a conceptualist who viewed the world from a mountaintop. His mind could bog down when confronted with a mass of details. He had a very spiritual outlook shaped by the cosmic beliefs of southwestern Indian tribes, particularly the Hopi and Apache.

No doubt his friend Immanuel Pardeahtan Trujillo, the Apache medicine man and head of the Native American Church, deeply influenced Bowart’s belief that psychedelics enhanced creativity by generating a harmonic resonance in the pathway between mind and soul. He was defensive about his education and confessed that his lover, Sherry Needham, taught him about the world by giving him books to read written by leading intellectuals, philosophers and political thinkers. Bowart had an almost psychic ability to foretell the subjects that would grip the public imagination. He was open, friendly and loved to talk about ideas.

Allen Katzman was a poets’ poet. He would sit patiently like a big brother rabbi, listening to the personal and professional problems of writers and offer them gentle consolation, advice and encouragement. He was The Other’s official spokesman because everyone agreed that he could handle the questions of even hostile reporters with an unflappable ease. Katzman had a poet’s ability to speak with footnotes, deftly scattering references from Plato to Plutarch to Pluto the dog like a farmer sowing seeds in a field of ideas. He was respected and liked by everyone.

Left to Right: Charlie Frick, Spain Rodriguez,

Peter Mikalajunas, and Peter Leggieri

Bill Beckman was the art director and he gave EVO a lot of its quirky, off-beat style. He taught me the art of paste-up, which involved gluing copy to a tabloid-size cardboard page imprinted with a non-reproducing light-blue grid pattern that aided the visual alignment of copy vertically and horizontally. Beckman’s weird, witty sense of humor (delivered in a soft Texas drawl) made working through the night enjoyable. (He can be heard on EVO’s “Electric Newspaper” album telling a barely audible dirty joke.)

About a month after I joined EVO, the paper nearly folded. During the paste-up of the issue, Bowart announced that there wasn’t enough money available to pay the printer. EVO was broke, and the printer had clearly demanded cash up front. Everyone was in a funk. Beckman completed the paste-up and left. I sat with Bowart, trying to cheer him up, but he remained deeply depressed and near tears.

It would prove to be the only time I would ever see him in such a state. As dawn came, our faithful printers agent, Woody Kosakow, showed up and I began pleading with him to intercede with the printer to get us a 48-hour extension on the payment. Woody said that was impossible. After some more pleading, Woody finally relented and agreed to pay the printer himself. It was a turning point in the life of EVO. The issue sold well and the paper was getting publicity in the press. A spread in the New York Times Sunday Magazine in July of 1966 increased EVO’s national exposure. I was selling more advertising and small paychecks became more regular.

The Swami

EVO seemed to turn everyone who worked there into a writer or an artist or both. I was no exception and was soon pressed into service creating visuals and writing stories (always using the in-house nom de plume, Irving Shushnick, invented by Allen Katzman). One day, Bowart took an acid trip and strolled into Tompkins Square Park where he saw a new East Villager, the Hare Krishna leader Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, dressed in golden robes and sitting in a lotus position under the giant tree that now bears his name. Bowart hurried back to the office in a “STOP THE PRESSES” fit, and began insisting that we immediately do a story about the “holy man” he had seen.

When Katzman pointed out that everyone was already working on an assignment, John Wilcock interjected, “Peter, you’re the only one with any theology. You do it.” I refused by pointing out that I was extremely busy and knew nothing about swamis. The three of them ganged up on me and, very reluctantly, I went off to meet the holy man. I did not like what I wrote and pleaded for time to do a rewrite. The three editors turned me down and the story went to press.

It wasn’t until some 35 years later that I learned the article is magnificently reproduced in the Hare Krishna’s main temple in India. The cover story was transformed into a life-size diorama that includes Walter Bredel’s photos. Apparently, Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada always credited EVO for the great success of his ministry in this world. To the best of my knowledge, The East Village Other is the only newspaper in the history of newspapers to be enshrined in a religious temple.

New York Times Sunday Magazine

The Owners

Toward the end of 1966, John Wilcock announced that he wanted to leave and spend his time writing his $5-A-Day travel books. (Yes, Virginia, you could tour Europe on five bucks a day!) He also wanted EVO to buy back his shares of stock in the corporation. At that time EVO owed me a lot of money in long overdue advertising commissions. A dilemma arose because EVO could not afford to pay both claims. An accord was reached: I was paid and I then gave the money to Wilcock for his stock. It was a case of two birds with one stone.

When I received the stock certificate, EVO’s accountant and business manager, Don Katzman, who was Allen Katzman’s twin brother, told me the corporation had issued 49 shares of stock. Bowart owned a majority 25 shares; I held 12 shares; and the remaining 12 shares were unevenly divided among Dan Rattiner, Allen Katzman, Don Katzman and Bill Beckman. I can’t recall if Sherry Needham was on the list of stockholders. In retrospect, stock ownership in EVO was never a matter of great importance. When Bowart left, he never really looked back (except for the abortive takeover bid), and, when I left, I didn’t either. The Other was a capitalist corporation in name only. In reality, it was an artistic collaboration.

At our next editorial meeting (editorial meetings were always very informal affairs) Katzman kidded me by asking, “Well, Pete, how does our new stockholder feel about the future of the corporation?” Bowart was laughing too, a locker room signal that I had made the team. I took the opportunity to outline EVO’s problems and the measures needed to correct them. Using a nautical analogy, I told them the ship needed a bigger hull to accommodate a bigger engine to achieve greater speed.

“Right now,” I said, “EVO is running mainly on the linear power of typewriters with only one light table as a graphics supercharger.” What we needed was a bank of light tables, each one manned by a graphic artist working to achieve a fusion of word and picture in a way that would elevate EVO to a new visual dimension. There was a silence. Then Bowart said, “Did you know Buckminster Fuller was a naval architect?”

“So what?” I responded, confused. “So for Pete’s sake, DO IT!” Katzman yelled. We all laughed.

The Rock Place

In the spring of 1967, I negotiated a “barter” lease with the owners of the Village Theater at 105 Second Avenue, near East Sixth Street. The lease provided us with 5,000 sq. ft. of space, heat and electricity in exchange for advertising space in the newspaper. We moved in, built a bank of light tables, constructed a large photography darkroom that also housed a stat camera and purchased our first headline machine. Finally, EVO had the room and the tools needed to grow and to fully experiment with the visual nature of a newspaper. Words and pictures were painted, bent, twisted, expanded, decomposed, scattered, exploded, compressed and obliterated. We created word clouds before there was a name for such a phenomenon.

Backstage party at the Fillmore East, 1970

The making of EVO had many spontaneous last-minute elements. No one knew before the paste-up process began exactly how an issue would look. Even cover visuals were conceived and created on the spur of moment.

In the summer of 1967, Bowart began spending less time at the paper, sometimes not even showing up for the all-important paste-up night when visuals were created, layout determined and the current issue achieved its final form. From the time EVO moved above the Village Theater, he had more or less left the running of The Other to Allen Katzman and me.

After an editorial meeting, Katzman asked Bowart about his absences. Bowart explained that he was feeling burned-out. Also, he had entered into a serious relationship with Peggy Hitchcock, a wealthy Mellon family heiress. He had become uncomfortable at EVO because his one-time live-in lover and muse, Sherry Needham, was still working there. The whole situation was too awkward for him to handle. I also believe he recognized that his management skills and temperament were unsuited to dealing with the problems a growing newspaper presented, particularly the difficult task of handling the sensitive egos of more than a dozen very creative artists.

When Bowart left EVO in November 1967, he rubber-stamped reality by naming me publisher and editor-in-chief. Katzman would continue as the paper’s editor. The two of us worked well together and continued our practice of dividing responsibility. Katzman was responsible for the writers while I managed the business and the production of the newspaper. Our close partnership would result in EVO’s “golden” time, a period of more than two years when circulation nearly doubled to more than 70,000, bills were paid on time and paychecks were regular.

In order to emphasize my belief that EVO was an artistic collaboration, titles were removed from the staff listing. The new office was sizzling with creativity and fun. Everyone seemed to stay there overtime because they didn’t want to miss out on the excitement of a non-stop party. EVO was a most interesting and happy place to work.

In January 1968 I made the decision to publish The Other on a weekly basis. Almost immediately we were struck by a catastrophe: our lease was automatically voided when the Village Theater declared bankruptcy and its mortgagor, Loews Corp., began a foreclosure proceeding. The building’s electricity was shut off, the boiler ceased functioning and the water pipes froze and burst, causing sheets of ice to form on the walls. No heat, no lights, no water, no toilets, and we had a paper to get out.

Miracle of the Hells Angels

It was a bitterly cold, dark and dreary night. Stalactite icicles hung precariously from the ceiling and a kerosene lantern was lit on my desk when there came walking into the room a handsomely dressed young man wearing an impeccably tailored dark overcoat with beaver trimmed collar, a bowler hat and carrying a real bumbershoot. He was the Loews attorney from the firm of Booth, Lipton & Lipton who had been sent down in response to my many, many increasingly profane phone calls that had upset his office.

Loews, he explained, was not responsible for the maintenance of the building until the foreclosure proceeding had wended its way through the courts, a process that could reasonably be expected to take many months. The Village Theater was responsible for all services and until such time… I cut him off. My voice screamed in a spittle spewing rage, “You DAMN WELL know that the theater is dead broke and you DAMN WELL know that Loews is the de facto landlord RIGHT NOW! I have people sick and I have a newspaper to publish!”

He was backed against the wall, clutching his umbrella to his chest, when a miracle occurred. In walked Spain Rodriguez followed by the chief officers of the Road Vultures and Hells Angels motorcycle clubs, all wearing their colors-emblazoned leather finery. “Is everything all right, Pete?’’ Spain asked as they all stared at the lawyer whose eyes bulged from their sockets while a look of total terror curdled his face. Instantly regaining my composure, I calmly directed the bikers to the back room. (I had forgotten that they had scheduled a meeting on EVO’s neutral ground to discuss a possible merger of the two clubs.)

I turned and whispered to the attorney, “If you don’t fix this place within 24 hours, those fine gentleman will lead a pitchfork-wielding mob of highly trained East Village protesters up to your office to lecture you on the common law, the law of the people and the law of the streets.” The poor guy ran out the door. However, the next morning the lights went on and a small army of plumbers and contractors were busy making repairs. They set the boiler thermostat on “high.”

A month or two later a dour-looking man came to my office and introduced himself as Bill Graham, the new owner of the theater which would be called The Fillmore East. “So this is The East Village Other. I’ve heard of you,” he said. He asked what our arrangement was with the previous landlord and I explained the “advertising for rent” barter agreement. He thought for a few seconds and said, “That’s fine with me.” We shook hands and never signed a written lease. He was, in my opinion, the perfect landlord. And he provided us with free, live music, performed by the world’s greatest rock bands in airshaft stereo.

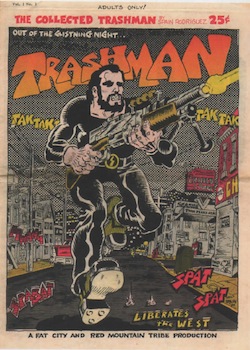

Cover by Spain Rodriguez

The Comix Revolution

The East Village Other began with an absolute commitment to freedom of thought, freedom of speech and freedom of the press. There would be no censorship in the content of its pages and no restrictions on free expression. Art should not be shackled to the norms of conformity. These libertarian values would be tested to the limit by a group of young, rebellious cartoonists who straggled into EVO, banded together into the underground art movement, and started the Comix Revolution.

The Other featured comics from the very beginning of its life. Bill Beckman drew the first underground strip, Captain High, featuring a character so stoned that his feet never touched the ground. During 1966, a very young Robert Crumb walked in and dropped off his earliest cartoons, some of which were drawn before he was 20 years old. Crumb was a wanderer, roaming from place to place across the country. He would show up unexpectedly with new work, stay for a while, and then take off again.

Next, Spain Rodriguez, wearing his Road Vultures leather biker jacket, rode in from Buffalo, New York, with his apocalyptic comics depicting motorcycle riding revolutionaries who fought for truth, justice, and the people, with help from the intergalactic world brain. He became a fixture at the paper and would surprise political debaters with his Marxist analysis of events.

In 1967, EVO published Rodriguez’s “Zodiac Mind Warp,” the first underground comic in tabloid newspaper format. Kim Deitch, Trina Robbins and Art Spiegelman followed Spain. By the time the paper had settled in above the Fillmore East, a who’s who of radical cartoonists could be found hanging out in EVO’s production room, the infamous Back Room: Vaughn Bode, Jay Lynch, S. Clay Wilson, Yossarian, Joel Beck, Roger Brand, Bhob Stewart, Gilbert Shelton, Bill Griffith and Willy Murphy were a few of the more than 36 artists whose comic strips would appear in the paper. At times it seemed like EVO was the underground cartoonists’ convention center, a place where they could meet, talk shop, exchange opinions and galvanize into a movement.

One of the focal points of the underground cartoonists was a shared hatred of the Comics Code, a 1950’s list of censorship practices designed to protect the nation’s youths from the evil effects of comic books. All comic books had to carry the Comics Code seal of approval. The underground cartoonists, however, seemed sworn to break its every rule. They wanted comics to be an adult medium of expression where any subject was a legitimate subject for visual discussion. They wanted to go where no pen dared go before and they did. There were no rules. They warned the world by calling their work COMIX, the “X” signifying adult content.

The Curse of the Gothic Blimp

In 1968 Vaughn Bode approached me with a plan to use the creative energy of the growing number of cartoonists by publishing a monthly comix newspaper that he would edit. Bode named it the Gothic Blimp Works and it was to be a publication of, by, and for the whole crew of cartoonists. After making arrangements for national distribution, I promised him I would not interfere with its editing or management in any way.

From the beginning, the Blimp had problems getting off the ground. Its inaugural issue, featuring a Robert Crumb cover, was four months late but received good reviews. The second issue was late and so was the third. By this time, Bode had passed the job of editing over to Kim Deitch, who then turned it over to others. The distributors were beginning to complain because their schedules were being disrupted by the Gothic Blimp’s untimely performance. After more than a year, only seven of the promised 12 issues had been published and the distributors were angry.

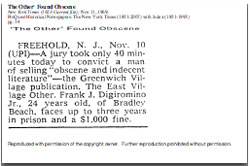

Despite these problems, the Gothic Blimp continued to receive rave reviews both nationally and internationally. However, by January 1970 the distributors were demanding an issue immediately or else they would cancel their contracts. At the same time, we received a warning from underground friends in the justice system that the Blimp was probably going to be “busted big time.” As a precaution, the No. 8 issue was made up of reprints from past EVO issues, the theory being that what had been published without complaint in the past could be republished again without complaint.

Peter Mikalajunas, one of EVO’s art directors, fondly known as “the Prince,” also served as an art director of the Gothic Blimp. On paste-up night, he selected the reprints for the No. 8 issue, arranged them in page order and began to design a new masthead for the cover that featured R. Crumb’s Mr. Natural as a vacuum cleaner salesman. The Prince and I were alone, waiting for sunrise when Don Lewis (another EVO art director) would arrive with our printer’s agent and take the Blimp to the printer. During the night, I had been talking to the Prince about the possibility of a police confiscation of the comix. Finally, Lewis arrived carrying a beer for the Prince. “Everything ready?” Lewis asked. “Wait a minute!” replied the Prince, who then affixed a picture of an ancient Egyptian death vulture to the masthead as the No. 8 issue of The Gothic Blimp Works was sealed into its box for transit to the printer and the world beyond.

“What’s that for, that vulture?” asked Lewis.

“It’s a sign that protects the Blimp from molestation by warning all would-be defilers that their souls will be cursed and cast upon the dung heap of eternity,” I said, “especially J. Edgar Hoover and Richard Milhous Nixon.” The Prince church-keyed the cap off the beer, passed it around, we each took a swig and said, “Amen.”

The next day, the police confiscated the entire issue, causing the death of the Gothic Blimp Works. And the names of Hoover and Nixon were permanently embedded in the dung heap of all eternity.

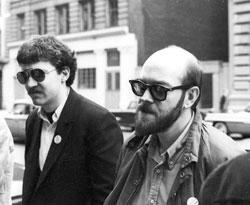

I, R, Crumb

EVO had founded the underground press and served as a major communications and coordination center for anti-war protest. Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, leaders of the Yippies, used EVO as a headquarters for planning demonstrations, including the infamous one at the 1968 Democratic national convention in Chicago. In fact, movement leaders of all kinds, including blacks and Native Americans seeking to right the injustices their people had suffered, came to EVO for help with their causes.

Postcard by R. Crumb

At any given time, artists and radicals from western and eastern Europe could be found talking politics at the Other. The young of the world were demanding freedom from intellectual repression and they sought to introduce underground journalism to their countries as a means to achieve that goal.

I was the only EVO editor to be arrested in the government’s secret Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO) aimed at eliminating leaders of the anti-war movement by destroying the underground press. Police surveillance by undercover agents and telephone wiretaps had identified me as a target.

During my good cop/bad cop interrogation, the bad cop placed a sturdy black suitcase on the table, opened it, and showed me its contents: about three dozen reels of audio tapes, each one banded with a white tape labeled “EVIDENCE.”

“We know everything you’ve been doing, Peter,” he said. “And what’s more, we know you’re Robert Crumb…and since your Crumb character has four outstanding felony warrants, you’re facing an additional 28 years in prison.”

“How did you come to the conclusion that I’m Robert Crumb?” I asked in a calm voice that utterly failed to mask the fact that my mind was screaming, “WHAT THE?????”

He then launched into a brain numbing, Sherlock Holmesian tour de force of gotcha sleuth logic that left me speechless because my jaw was locked in a permanent, down, wide open position. The police, he explained, were finally “hip” to the underground press’s use of the “put-on,” designed to send the authorities off on a wild goose chase and give them fits of apoplexy. He ticked off a list of hoaxes: attempting to exorcise evil spirits by levitating the Pentagon with a Druid force field; threatening to put LSD into the drinking water supply in order to induce the mass hallucination of the population; and advocating the smoking of bananas to achieve a hallucinogenic “high.”

Plus, they had been searching for Crumb for a very, very long time and they couldn’t find him. Although everyone in America had an address, he had no known address. They knew that EVO used the names of fictional writers and artists. The name “R. Crumb” was too cartoony to be real. And they had seen his self-portraits, which looked to them like a cross between Goofy and Arnold Stang (a 1940’s Hollywood comic actor) — and no one could look like that! He concluded, with Aristotelian certitude, that since Crumb was a fictional hoax, and since I always had Crumb cartoons, I must be Robert Crumb.

Bert Neuborne of the New York Civil Liberties Union was my lawyer. The DA handling the case seemed to want no part of the fiasco. All charges were dropped in the best interests of justice. I learned that taking one for the team was no fun, even when it was funny.

Epilouge

The Other was a happy ship but her message of peace, freedom of thought and freedom of expression earned her some very fearsome enemies. The cloaked forces of the Dark Empires pursued her and sought to destroy her: the FBI, the CIA, MI-5, the KGB and the Vatican. EVO’s news dealers endured more than 141 arrests and seizures; and her national advertisers were advised that she was on the government’s Black List. The paper’s phones were wiretapped and her offices under surveillance by undercover police. That any newspaper could survive such an awesome onslaught for so long is a testament to the magic of the Other.