Why EVO Mattered

by Abe Peck

Starting in the mid-1960s, in the zone between 14th Street and Houston, First Avenue and the Alphabet blocks, a wave of longhairs began joining Ukrainians, Puerto Ricans, and pockets of poets, writers and artists. Ingestive preferences turned the grey streets Technicolor. So what if one of my roomie’s father would tell us, “I moved out of a better apartment in this neighborhood in 1924.” We were self-proclaimed life artists, merrily donating our belongings to local intruders into our happy hovels. We were home.

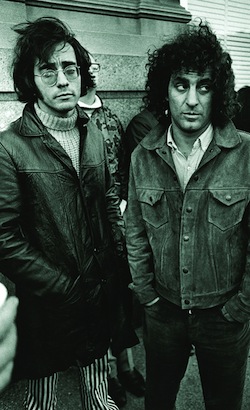

Abe Peck and Abbie Hoffman

The East Village was where I experienced the end of grad school and the Army Reserves and the start of a community I could call my own. Where I became closer to Sergeant Pepper than to my master sergeant. Where EVO – The East Village Other – mattered.

The Village Voice was literate, and had the apartment ads. But from 1964 to 1973, hundreds of underground newspapers sprang up in every city and college town, and within high schools, the military and even prisons. They varied, but all provided a bent-mirror image of what the dailies and TV news and Time offered: herbs were fine, sex was cool, the Vietnam War sucked, racism was for losers.

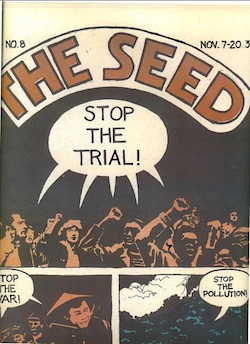

Like The San Francisco Oracle (though not as third-eye-y) or my eventual underground-press homeland, the colorful Chicago Seed, EVO began, in late 1965, to chronicle an urban tribe. “We hope to become the mirror of opinion of the new citizenry of the East Village,” EVO declared in its first issue.

While EVO covered political demonstrations from inside the barricades, its sensibility stood within the “Head” rather than the “Fist” camp of the papers, more peace sign than clenched fist. EVO portrayed “business as un usual.” The freshest bands. Tim Leary’s pronouncements. The latest tussle over Tompkins Square Park. EVO was where my crew first heard the siren song of the Haight-Ashbury, which sent us apprentice Kerouacs off to the Summer of Love.

EVO literally colored outside the lines. Its graphics got gritty, but its collages and psychedelic illos reflected what we were seeing with our eyes closed. The paper captured the energy of late-‘60s New York City: at once full of promise and falling apart. Its comix eschewed Dick Tracy for Spain Rodriguez’s “Trashman,” an apocalyptic melding of biker gangs and left-wing politics.

Third, EVO helped birth the Underground Press Syndicate, an alternative force-multiplier through which papers exchanged stories without charge – and pumped themselves up. “We’re no community paper,” editor Allen Katzman said in 1967. “We’re a worldwide movement for art, peace, civil rights, morality in politics.”

Stories could be incisive and zingy, credulous or spacey, fueled by onsite reporting or conspiracy theories. But the mainstream’s “official reality,” however well-crafted, too often accepted government lies and material acquisitiveness, while the underground press, initially at least, was based on moving lightly across the planet. Those of us who worked on underground papers were learning as we went, but strove to be amateurs in the best sense — amore , to love.

The Chicago Seed

EVO bore witness: we are a tribe; here is our journey. Through the 1968 Democratic Convention, underground papers freely debated the best way to build a lifestyle and protest the war. Things changed after the collapse of the Haight and the police snuff in Chicago, but “EVO kept right on creating images, reinforcing the hip consciousness long after the urban utopias of the hip world had dissipated, strung out on too much reality,” wrote Laurence Leamer in “The Paper Revolutionaries,” the best contemporary book about the papers.

Circulation rose to a reputed 65,000 by 1969 and EVO would offer strong coverage of the (Black) Panther 21 trial, but the bloom was dropping off the psychedelic rose. The Rat emerged in 1968 as a more political alternative, and then was seized by feminists tired of an underground sexism also found at EVO. As Craigslist would disaggregate today’s press by siphoning off classified advertising, so testosteronic sex papers like Screw out-raunched EVO and captured the sizable horn dog readership and — unseemly as the topic was — a good chunk of working capital.

The Politics of Free showed its limits. A shift from Let it Be to Let it Bleed circled the wagons and shifted the papers toward what EVO writer Lennox Raphael called “flatirons of defense.” Readers were moving on, toward straight jobs and a second pair of jeans. “People just overloaded. You had to come down, come to a state of rest and start to absorb all the changes,” Katzman would recall.

By 1972, EVO was over.

When I went on to work at Rolling Stone, a colleague dismissed the underground press as a group of “noble failures.” But for some golden years, EVO allowed us to dream big, New York-style.

Abe Peck is the author of “Uncovering the Sixties: The Life and Times of the Underground Press”.