Where Underground Comix Lurched Into Life

by Patrick Rosenkranz

I never worked for The East Village Other but I was a captivated reader from the first time I picked up an issue in 1966. As an 18-year-old naïve Catholic scholarship student at Columbia University, I was ripe for the revolution. My roommate introduced me to smoking dope that winter and my enhanced appetite often drew me to the student cafeteria, where I couldn’t help but be attracted to the radical contingent from Students for a Democratic Society sitting around their regular table. They looked to my eyes like bomb-throwing anarchists who were having wild sex every night. They often left behind copies of The East Village Other, which I picked up. It was love at first sight.

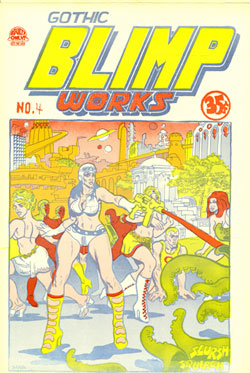

Cover of the first Gothic Blimp Works issue, by Robert Crumb

I’d never seen a publication like this before. It was full of wild accusations and bawdy language and doctored photographs. It had President Johnson’s head in a toilet bowl. It had naked Slum Goddesses, truly bizarre personal ads, and a whole different slant on the anti-war movement than my hometown paper upstate. But best of all, it had the most outrageous comic strips. The continuing saga of Captain High; the psychedelic adventures of Sunshine Girl and Zoroaster the Mad Mouse; Trashman offing the pigs and scoring babes left and right. While I enjoyed many aspects of EVO, I liked the comics the most.

Bill Beckman was one of the first cartoonists with his counterculture crusader Captain High, whose main mission was to get high and stay high. Beckman didn’t draw very well, but EVO’s readership could relate to the premise. Beckman contacted his buddy Gilbert Shelton from back at the University of Texas at Austin, who mailed in an occasional strip called Clang Honk Tweet!; Hurricane Nancy Kalish contributed a spacey, Aubrey Beardsley-style comic called Gentle’s Tripout. Others came and went without much notice until Walter Bowart commissioned Manuel “Spain” Rodriguez to draw a 24-page all-comic tabloid, which he published as Zodiac Mindwarp in 1966.

“With that, EVO was stuck with me,” said Spain. “I started doing all kinds of artwork and comics for them,” including his first cover for the July 15, 1966 issue. “EVO was the perfect vehicle for an early cartoonist. It really served my purposes well because I could do whatever I wanted and get paid for it, which was impossible in the straight comic thing of the time.” There were some downsides. Sometimes his comics were bumped to make room for other stories, and some editors tried to tell him what to draw, or worse, what not to draw.

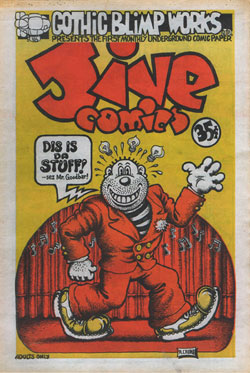

Cover by Robert Crumb

He brought on EVO’s virgin bust with his “Brink of Doom” comic strip in the Feb. 2, 1968 issue. It showed Big Rod Pernil going downtown on young Kathy Nesbitt, with a SLURGIL, SHLOSH, SHLURP sound effect balloon. The Brooklyn District Attorney had a news vendor arrested for selling obscene material and seized a thousand copies of that week’s issue. In the next edition, Spain put the offending panel on the cover as a connect-the-dots drawing and invited readers to send their completed puzzles to D.A. Aaron Koota.

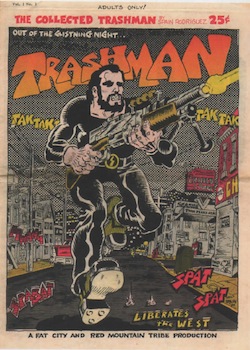

Eventually, Spain came up with a continuing character that perfectly merged his political persuasions with his interest in macho adventure fantasies, Trashman, Agent of the Sixth International, who with his band of comrades-in-arms struggled to overthrow a corrupt plutocracy. “The strips we were doing really helped the circulation of EVO,” he insisted. “Some people will buy a newspaper just to buy a comic strip.”

Kim Deitch came to New York late in 1966, and seeing that EVO published comics, decided to try his hand at it. He pitched a strip called Sunshine Girl to editor Allen Katzman, about a semi-mystical embodiment of all that was fresh and exciting in the emerging drug culture. She was the daughter of a god, come to earth through the parentage of a duck, a flower, and a clown, to do battle with the forces of evil. “When I showed them at the EVO offices, they went over like gangbusters,” said Deitch. “I was in! Published. No pay, but what did I care?” Once in a while, Bowart would flash him a little green, he recalled, but it wasn’t until Joel Fabrikant ran things that Deitch got on the payroll.

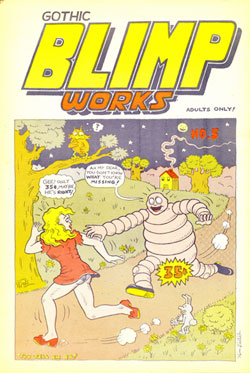

Cover by Spain Rodriguez

One day in spring 1968, Deitch dropped into EVO to see if he had any orders for Sunshine Girl buttons from his classified ad. Fabrikant corralled him in his office, offered him a joint, and sent someone to get Spain Rodriguez. Fabrikant asked him, “Spain, don’t I pay you $40 to do a weekly comic strip and other illustrations as needed?”

“Yeah, right,” answered Spain.

“Joel looked my way with a penetrating stare,” said Deitch. “He wasn’t flat out offering the same deal, but the implication that it could be had was fairly clear.” Deitch was soon drawing full time at the paper, and these early years in the underground press propelled him on his life’s career. “That was better than any college education. I would do a strip and then just pitch in in any way, shape, or form to get the issue out. Once in a while me or Spain or somebody would have to go down to New Jersey to oversee the printing. But believe me, that was the best offer that any young artist could get.”

Robert Crumb was drawing greeting cards in Cleveland when Ralph Ginzburg invited him to produce some comic strips for his snooty new magazine, Avant Garde, in 1967, but Crumb’s efforts did not please the publisher, who wanted something “more cohesive” with a stronger “story line.”

Art by Spain Rodriguez

“Ralphy didn’t appreciate Av ‘n’ Gar Comix. What a square,” said Crumb, who promptly trucked on down to the Lower East Side and dropped his seven pages on Walter Bowart’s desk. Bowart printed all of them over the next several weeks. From there, they went all over North America and Western Europe through the aegis of the Underground Press Syndicate, and sealed Crumb’s lifelong affinity for subterranean publishers. He had already garnered some national exposure in Cavalier and Help! magazines, but this was truly the first time his work found its target audience.

Many of his major characters made their earliest appearances in EVO – Mr. Natural, Flakey Foont, Av ‘N’ Gar, The Old Pooperoo, Shuman the Human, Angelfood McSpade – even a semi-autobiographical married couple, Edgar and Mary Jane Crump. On his occasional visits to New York during the next several years, he was heartily encouraged to create comics for EVO. Its editors quickly realized that a Crumb cover meant better sales. “They would print anything that was halfway readable,” recalled Crumb. “There was no censorship.” Hence, pages like Phonus Balonus Blues. Said Crumb, “Nobody would blink. They were happy to print anything outrageous.”

Art Spiegelman was still at the High School of Art and Design when he submitted his first comic strips to EVO but Katzman turned him down and advised him to get some actual experience with drugs and sex first. He took that advice to heart and showed up again a few years later with a character who claimed it was “a treat to beat your meat on the Mississippi mud.”

Alan Shenker, who signed his work Yossarian was another contributor, as was Trina Robbins, Willy Mendes, Jay Kinney, Bill Griffith, and Vaughn Bodé, who were also recruited to do work for the rest of the EVO publishing empire, which included Kiss, Aquarian Agent, and Gay Power. There was also work available at the other new underground papers appearing around the city – Screw, Rat, Pleasure, and the New York Ace. It was a time of growth for cartoonists in the counterculture press, and the straight comic publishers at Marvel and DC were taking notice.

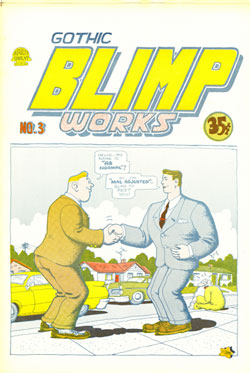

Cover by Kim Deitch

In 1969 EVO rolled out an all-comic tabloid extravaganza with full-sized color pages, just like in the early days of the medium when The Katzenjammer Kids and Little Nemo and other strips were grandly presented in turn-of-the-twentieth-century Sunday funnies. Many contributors argued instead for a comic book format since Zap Comix and Bijou Funnies and Feds ‘n’ Heads had already appeared, and there were numerous discussions about the title as well. Crumb, who drew the first cover, wanted to call it Jive Comics, but editor Vaughn Bodé had the final say, and he slapped his logo for Gothic Blimp Works across the top of Crumb’s design on the first issue.

Everybody in comics wanted in, even the younger artists working in the overground industry like Bhob Stewart, Bernie Wrightson, Ralph Reese, and Mike Kaluta. Many of the West Coast counterculture cartoonists sent work too, including S. Clay Wilson, George Metzger, Rory Hayes, and Robert Williams. After Vaughn Bodé edited the first edition, Kim Deitch took over the job. By July, he had amassed so much original art that he decided to stage a show in a storefront at 335 East Ninth Street. Joel Fabrikant got paid for some weird deal with a giant bag of Sunshine LSD that week, he recalled, so he was enjoying it on a daily basis and sharing it with his comic museum visitors. The underground art was supplemented with original artwork by Jack Davis, Wally Wood, Frank Frazetta and Windsor McCay.

Gothic Blimp Works did not carry the sex ads that had become an ugly but necessary advertising niche for the underground press, and consequently were not as valued by the magazine distribution networks, who also had a stake in the burgeoning sex industry. There were problems getting shelf space in newsstands and smoke shops. The amount of work also took a toll on Deitch, and by the end of that year, most of the EVO cartoonists opted to move to San Francisco, where underground comix were really taking off. Rip Off Press, Print Mint, Apex Novelties, and other new independent publishers were printing comic books as fast as they could, and had their own alternative distribution systems that bypassed the traditional routes.

Cover by Art Spiegelman

Jay Kinney, who was then new to cartooning, watched them go with regret. “When the cartoonists decided to move to San Francisco (the people, who to my mind were the cream of the crop of the underground), there was a rapid decline in EVO.” The biggest disappointment to Kinney was that the New York underground press went out with a whimper, not a bang.

It was only afterwards that I realized I had witnessed the renaissance that was the underground comix movement. As a young writer looking for a suitable topic for my first book, I decided to chronicle these new comix. I sought out and interviewed as many of the cartoonists as I could find and recorded their strange and wonderful stories. Following many trials and tribulations, my work appeared as Artsy Fartsy Funnies in 1974, published by Paranoia Press in The Netherlands.

Many years later, I got an unexpected call from Kitchen Sink Press. The editor, Robert Boyd, said he was holding a copy of that book in his hands and wanted me to write something bigger and better. I’d been waiting 25 years for someone to ask me that, and immediately agreed. A few more trials and tribulations later, the hardcover book came out in 2002 from Fantagraphics Books as “Rebel Visions: The Underground Comix Revolution 1963-1975.”

Patrick Rosenkranz is the author of “Rebel Visions: The Underground Comix Revolution 1963-1975” and has written biographical retrospectives of Rand Holmes and Greg Irons and is currently at work on one of S. Clay Wilson. His website is patrickrosenkranz.com.