Ed Sanders on EVO and ‘The New Vision’

by Ed Sanders

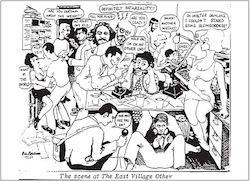

Drawing by Bill Beckman, Nov. 1966.

I first knew Walter Bowart around 1963 or ’64 when he was a bartender at Stanley’s Bar, located at 12th Street and Avenue B. Bowart was an artist who did some design work in early 1965 for LeMar, the Committee to Legalize Marijuana, which operated out of my Peace Eye Bookstore located in a former Kosher meat store on East 10th Street between Avenues B and C.

Allen Katzman I had known since 1961 when he helped run open readings at various east-side coffee houses, such as Les Deux Magots on East Seventh, and later the Cafe Le Metro on Second Avenue. Katzman was known at the time mainly as a poet. (During his time at EVO, Katzman spelled his first name Allan.)

During the summer of 1965, Bowart, Katzman and others, including the artist Bill Beckman, Ishmael Reed, Jaakov Kohn, and Sherry Needham, decided to found a newspaper. Poet Ted Berrigan, as I recall, came up with the name, The East Village Other, with “Other” coming, of course, from Rimbaud’s famous line of 1871, “Je est un autre,” I is an Other. Another account has Ishmael Reed coining the name. (The participants in the Dada movement argued for 50 years over who first thought of the name “Dada.”)

Bowart and Katzman invited me to join as a part-owner. I meditated seriously about jumping into the EVO project. In the end I turned it down because of all my activities — underground filmmaking, publishing, running the Peace Eye Bookstore, singing with the Fugs, my family, and writing poetry.

The Fugs, the band I led, was on a cross-country anti-Vietnam War tour during the fall of 1965 when EVO first began publishing. It began in October as a monthly, then a biweekly, and finally as a weekly.

There were tens upon tens, and maybe hundreds of people who were part of EVO, as contributors, staff people, artists, distributors, lay-out artists, and just those who liked to hang out and party on the periphery during paste-up and publication nights. Early East Village Other contributors included Ishmael Reed, Allan Katzman, John Wilcock and Bill Beckman, with his Captain High cartoon panels. Beckman would soon design the Fugs stage set at the Astor Place Playhouse.

Allen Katzman, Bill Beckman, Walter Bowart

In his memoir, “The Perfect Agent: An Autobiography of the Sixties,” Allen Katzman lists some of those involved with the paper: “Various people helped us with the endeavor: Bill Beckman, Jim Brodey, Rod McDonald, D.A. Latimer, Spain Rodriguez, John Wilcock, Eve Babitz, Paula Sherwood, Ray Schultz, Don Lewis, Peter Legierri, Lil Picard, Peter Mikaulunas, Jaakov and Stephen Kohn, Linda, Zod, Fred, Vinnie, Lita Eliscu, the Cocaine Twins, Robert Crumb, and a cast of thousands.”

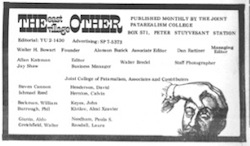

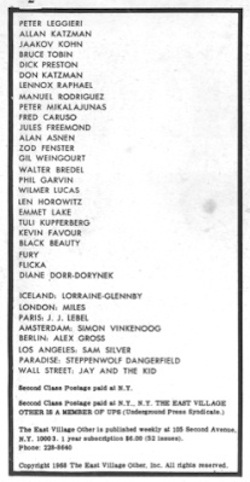

Below are two staff listings, one from November of 1965, the other from 1968 — to show the multitude of people associated with EVO.

How much did EVO cost back then? 25¢ a copy for the early issues, later reduced to 15¢. A feature of early EVO issues was a Slum Goddess pictorial, inspired by the Fugs tune.

Around the nation were what they called web presses, sturdy printing machines with large rolls of newsprint attached, which normally were used to print used car brochures, college newspapers, and the like. There was always a slot in the production schedules for these web presses to print almost anything anybody wanted, including the burgeoning Underground Press. According to Coca Crystal, who wrote for and worked on production for EVO, the paper was first printed at a press in Bordentown, New Jersey. “And the final one,” she told me, “was in Long Island City. We had a printers agent named Woody who took care of the business end of the printing.”

In addition to The East Village Other, underground newspapers began to flourish, including the Los Angeles Free Press, Chicago Seed, San Francisco Oracle, Milwaukee Kaleidoscope, Detroit’s Fifth Estate, Berkeley Barb, Georgia Straight, Great Speckled Bird and others. They were part of the glory of the ’60s brought to us by the unused portions of the great Bill of Rights.

EVO became a soapbox for The New Vision. It was part of a generation that fervently believed that important and long-lasting changes would occur in the United States which would bring free medical care to all, affordable rents, great art and great music, plus an end to war and the growth of personal freedom and good vibes. It also pioneered a brilliant collage/montage feel to the design and layout of the paper. The earliest issues of EVO featured the Captain High cartoons of Bill Beckman. Soon the excellent artwork of underground comic artists such as Spain Rodriguez, Kim Deitch, Trina Robbins, Art Spiegelman, R. Crumb and other comic artists graced EVO’s designs and pages.

In 1967, EVO moved its offices from 147 Avenue A to 105 Second Avenue, above the Village Theater, which in early 1968 would become Bill Graham’s Fillmore East.

Reading various accounts of the era, it’s obvious how fantastically complicated was the history of EVO, and the comings, tenures, squabbles and departures of its many participants.

The American Secret Police Go Against the Funding of the Underground Press

When underground papers such as EVO, The L.A. Free Press, and The Berkeley Barb became more and more successful, the war machine became disturbed over the success, and in August of 1967 the CIA began its ultrasecret program called Operation Chaos in order to find ways to stymie the anti-war Left.

The Underground Press was one of the Chaos program’s targets. Around October of ’68 a Chaos-program analyst whacked out a memo which noted “the apparent freedom and ease in which filth, slanderous and libelous statements, and what appear to be almost treasonous anti-establishment propaganda is allowed to circulate” in underground papers. The CIA smut sleuth then suggested a strategy for silencing the underground. “Eight out of ten,” he wrote, “would fail if a few phonograph record companies stopped advertising in them.”

The CIA of course denies it directly carried out the concept of interdicting the record company money stream. Instead, the FBI did it. In January of ’69 the San Francisco office of the FBI wrote to headquarters that Columbia Records by advertising in the underground “appears to be giving active aid and comfort to enemies of the United States.” The memo suggested the FBI persuade Columbia Records to stop advertising in the underground press.

It worked. By the end of the next year, 1971, many record company ads had been pulled and a number of underground papers had folded.

It will probably never be known whether, or to what extent, the CIA/FBI’s attack on the underground press harmed the The East Village Other. In the memoirs of Allen Katzman and Coca Crystal, certain inner squabbles at EVO were described. They were probably parallel phenomena — the U.S. government’s clandestine attack on the underground newspapers, and the squabbles that seemed to erupt across the country in 1970 and 1971 which impinged on, say, The Los Angeles Free Press and The East Village Other.

The larger political picture of the Kent State Massacre of May of 1970, and the May Day Demonstrations in D.C. in 1971 were signposts of the turbulence underway in the United States. EVO was rocked in this climate. For instance, in her interesting memoir/diary, Coca Crystal describes her activities for August 4, 1970 as follows: “Paste up was uneventful. Monday there was a meeting at Alternative University for a collective that wanted to take over EVO. There were people from Rat, The Herald Tribune, the New City Free Press, and The Liberated Guardian, and countless others as yet unlabelled. Four EVO staffers were there. Ray, Joe, Charlie Frick and myself, and we stood under heavy fire of accusations against EVO.

“They claimed EVO isn’t community-oriented enough and is a capitalist venture to boot. They had some good ideas and we talked for a long time. It was decided, by them, that they should put out the next issue. They decided to come to the EVO meeting the next day to talk about their plans to the staff of EVO.” (Someone should publish Crystal’s memoir.)

Allen Katzman on the Demise of The East Village Other

In his 191-page book manuscript, “The Perfect Agent: An Autobiography of the Sixties,” Allen Katzman described the demise of The East Village Other: “Kent State and Attica transfixed the ‘movement.’ The underground press suffered binary fission as editorial and political collectives paired off into separate entities. Older leaders, such as Abbie Hoffman, were roasted by internal political scandals and unsubstantiated grudges.

“My newspaper was not exempt. The Other was split apart, polarized by young against old, right against wrong, the group against the individual.

“Accusations replaced news reporting as the expression of events. It took on a momentum of its own. I left, and let EVO to die a natural death.” (After he left EVO, Katzman moved to Woodstock, New York.)

Coca Crystal herself paid for the printing costs of the final two issues, and the brilliant project came to an end sometime in March of 1972, three months before the Watergate break-in.