When Matuor Alier first started experiencing symptoms of COVID-19 in mid-October, he quickly took steps to isolate himself from his community in Fargo, a city on North Dakota’s eastern border with Minnesota.

Alier, a 32-year-old social worker who came to North Dakota in 2008 as a refugee from what is now South Sudan, was able to work from home while he was ill, quarantining in his home while enduring chills and fits of coughing. But the experience made him even more aware of how difficult dealing with COVID-19 was for other members of his community: North Dakota’s growing population of refugees and immigrants, particularly from Africa.

“When the pandemic hit in March, they weren’t getting the information,” Alier said. “They were not understanding what was going on.”

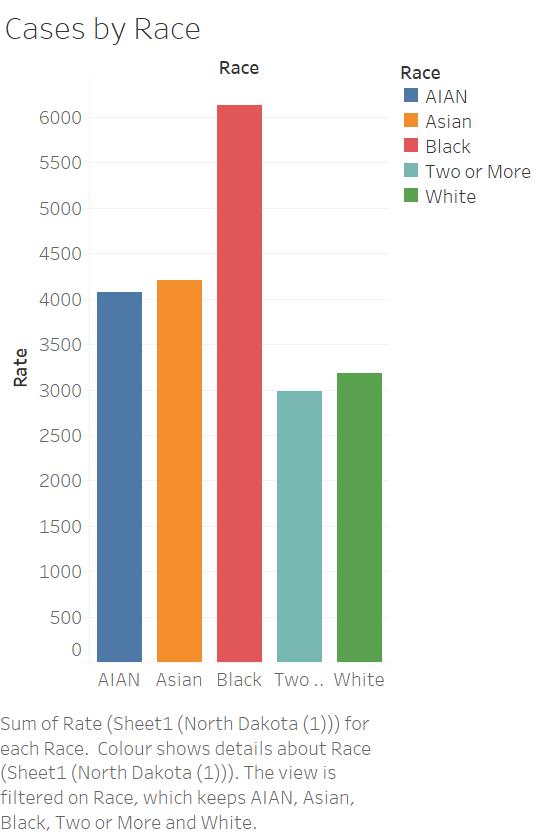

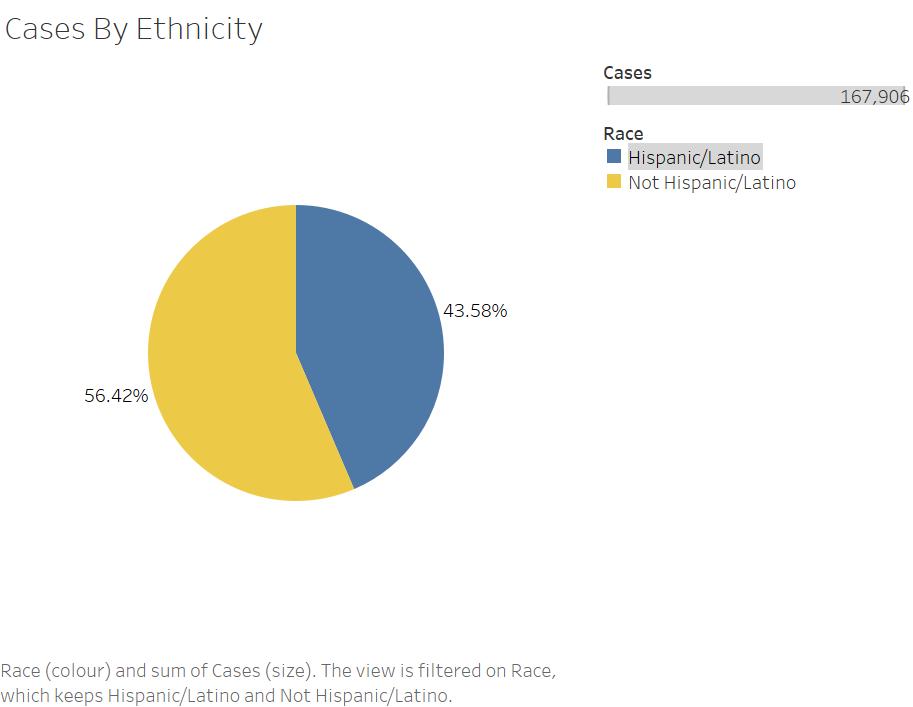

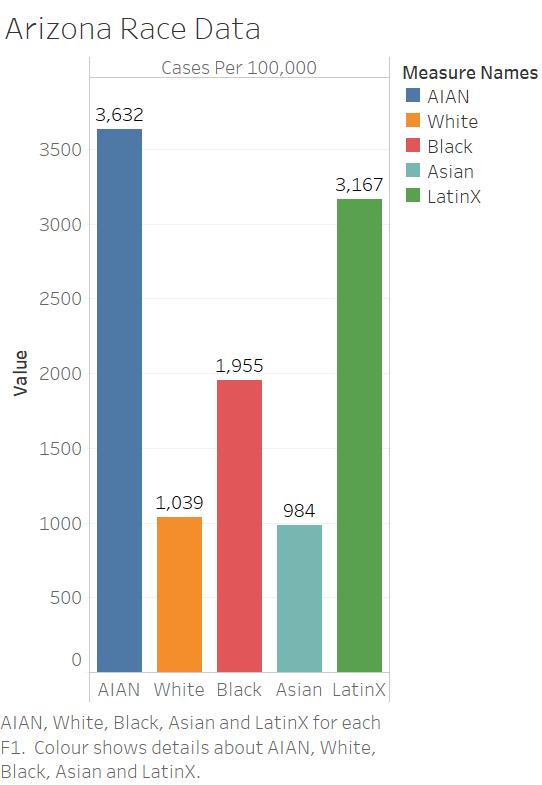

According to the latest data from the COVID Tracking Project, Black North Dakotans had the highest rate of COVID-19 cases relative to their population in the state, eclipsing even other vulnerable groups such as Native Americans. While the state does not release racial data for deaths from COVID-19, the infection rate is over 9,600 per 100,000 for Black people, compared to about 6,700 for people identifying as white, as seen in the chart below.

These numbers reflect what activists and government officials have seen in the state as the virus has devastated African immigrant communities. North Dakota has endured a wave of infections in the fall, and currently has the highest case rate in the nation, but immigrants are particularly vulnerable to the virus due to higher rates of poverty and language barriers that prevent them from getting information about COVID-19.

In response, nonprofit organizations and volunteer groups dedicated to helping immigrants and refugees in North Dakota have stepped up to provide groceries, safe spaces to quarantine and translation assistance for non-English speakers seeking information about COVID-19.

“They don’t speak the language, they don’t have anybody advocating for them,” said Clarissa C. Van Eps, president of the North Dakota chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, or NAACP. “We’re telling them that they have a safe space with us and telling them the things that we can do for them if needed.”

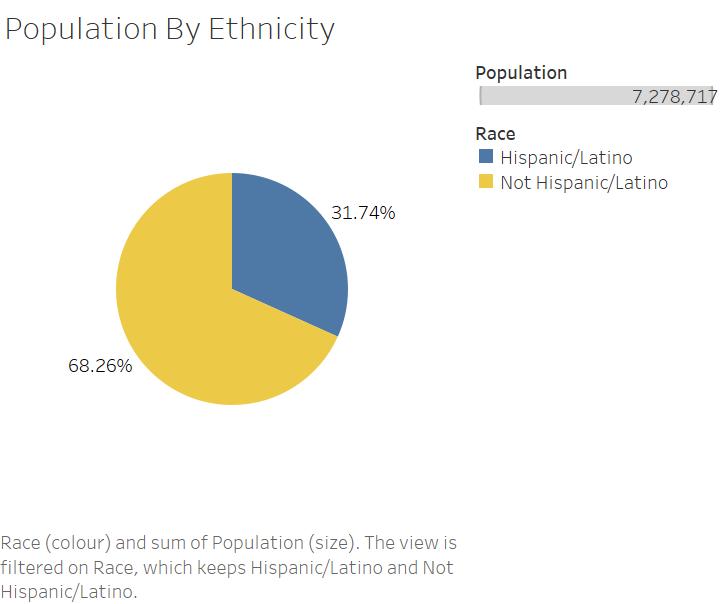

Nationwide, people of color have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19 due to a range of factors, including poverty, essential worker status and pre-existing health conditions. But the racial disparity in COVID-19 infections in North Dakota reflects larger trends particular to the state, which has experienced rapid demographic change in recent years. Over the past decade, the population of North Dakotans identifying as a race other than white has grown from just under 10 percent to 13 percent.

The largest growth has been in the Black community, whose numbers have more than tripled since 2010, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

The majority of this increase is driven by growing numbers of “New Americans” — a catch-all term for immigrants and refugees who have come to North Dakota seeking economic opportunity or political asylum. The percentage of foreign-born North Dakotans stood at 4.7 percent in 2018, up from just under 2 percent in 2000. While the state has significant populations of Asian immigrants, including Bhutanese refugees, the largest group identifies as Black, and includes immigrants from Somalia, Sudan, Liberia, Eritrea and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

With a population of about 125,000, Fargo is North Dakota’s largest and most diverse city, and reflects many of these recent demographic trends. The city’s plentiful jobs in the manufacturing and healthcare industries, along with a relatively low cost of living, have attracted waves of immigrants, while North Dakota as a whole leads the country in refugee resettlement per capita.

But some of the very opportunities that pull New Americans to the region also make them more vulnerable to COVID-19, according to Hukun Dabar, executive director of the Afro-American Development Association of Fargo-Moorhead. Immigrants working manufacturing or retail jobs cannot work from home, while those in the healthcare industry spend more time in COVID-19 hotspots such as nursing homes and hospitals. Immigrant communities tend to be lower-income and less likely to own their own homes, while the state of North Dakota did not enact a rent moratorium during the pandemic.

“At the end of the month, the landlord wants the rent,” Dabar said. “They can’t stay home even one day from work, because they have kids to feed, they have rent to pay, they have bills to pay.”

Cultural and social factors heightened their vulnerability. Stigma against immigrants — who were sometimes blamed for spreading COVID-19, Dabar said — led some to avoid reporting their symptoms, while language barriers caused a general lack of information about the virus and its effects. Many immigrant families also live in large, multi-generational households where one infected person can spread the virus to multiple others, Dabar added.

To address these complex issues, nonprofit and volunteer groups have played a prominent role. Alier helped found the ESHARA Project — which stands for Ethnic Self Help Alliance for Refugee Assistance, and brings together seven community-based nonprofit organizations in the Fargo area — in 2016 as an employment assistance program for New Americans, and worked on pivoting the coalition to COVID-19 response in June. Throughout June and July, ESHARA coalition members helped nearly 300 people with rental assistance, grocery delivery services, and help getting tested for COVID-19 or filing for unemployment benefits.

Other groups have also stepped in to help, including the North Dakota chapter of the NAACP. The chapter, which was only created a few months ago in the wake of nationwide protests over racial justice and is still in the process of joining the national NAACP organization, has mustered volunteers and funds to distribute groceries and provide places to quarantine, according to Faith Shields-Dixon, the group’s vice president.

But it’s been difficult to see the disease ravage immigrant communities across the state, she noted.

“We’ve seen some loss of life — some of the pillars of the community have passed away from COVID,” Shields-Dixon said. “Everywhere people are dying from this disease. But we know that being able to provide those extra resources can lift the load off of them, and be able to assist them during this tragic time.”

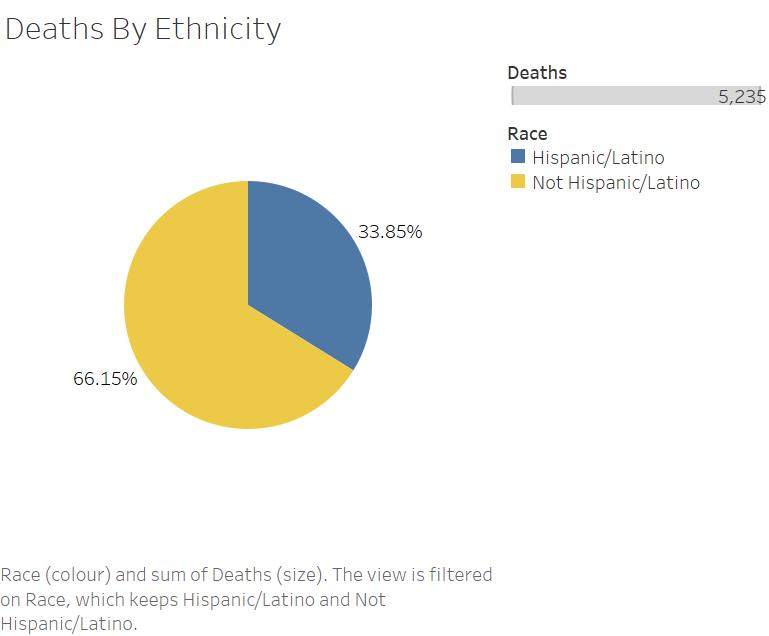

Death data by race is unavailable in the state because the number of deaths among people of color is so small that releasing it would potentially allow individuals to be identified, a violation of health privacy regulations, said Grace Njau, an epidemiologist at the North Dakota Department of Health. But she said that despite the high rate of COVID-19 cases among New Americans, the rate of deaths for this population tends to be low because they are often younger and healthier than other groups.

At the same time, Njau said steps taken by the state to combat the virus can benefit all who are impacted by it. On November 14, North Dakota Gov. Doug Burgum implemented a statewide mask mandate and announced new restrictions on social gatherings for the first time since the start of the pandemic, complementing requirements that already existed in larger cities like Fargo and Bismarck. Njau said she sees this as a positive sign, and that the rate of new infections has already begun to drop.

“For now, I’m a little bit more optimistic in terms of our outlook,” Njau said. “But how long it lasts depends on how long we can keep up our masking and social distancing. If things hold at a steady state of where we’re at currently, I would say we’re heading in a positive direction.”

But even if cases drop, challenges will remain for New American communities in particular. Dabar said the state needs to provide more assistance to small business owners — many of whom are immigrants — facing losses due to COVID-19, while Alier added that children of immigrants tend to struggle with distance learning because their parents may not be able to afford the technology or help them if they don’t speak English.

“New Americans are taxpayers, they go to work every day, and they’re not people who always depend on benefits,” Dabar said. “So they need to see them as neighbors. They’re a big part of the state of North Dakota, because they’re not going anywhere.”