“Alexa, is that all there is?”

Smart voice interface is a promising new platform, but newsrooms haven’t done much with it.

Don’t be surprised if you receive an Amazon Echo or a Google Home as a birthday present—a recent report predicts that smart speakers will be in more than half of households in the U.S. by 2022. The smart speaker is trending, and voice interface is gaining attention.

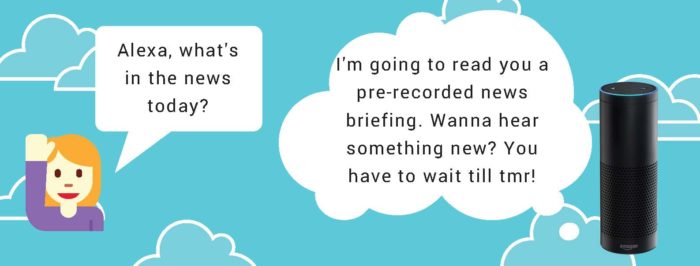

Newsrooms have started to build flash-briefing skills—the voice-driven apps recognized by Amazon’s voice assistant, Alexa—which give users easy access to the daily news just by asking, “Alexa, what’s in the news today?”

Imagine millions of users posing that question every morning. But currently Alexa—or any other smart voice interface—is not the best option for news consumption. At this point smart speakers provide a less autonomous experience as well as less-informative (and often more time-consuming) content than you can easily find on a smartphone. Yet the potential of voice interface should not be underestimated. Talking to machines will likely become a common way of life.

What’s out there?

News features on smart voice interface vary. Take Amazon Echo as an example. The most common flash-briefing skills are pre-recorded audios of the day’s headlines, but users can hear the news summaries from different sources in their order of preference, which they can set up in the Alexa app. By the end of 2017, there were more than 4,000 flash-briefing skills available for Alexa. Here’s a representative sampling.

The old schools: The New York Times, CNN, The Wall Street Journal, NPR

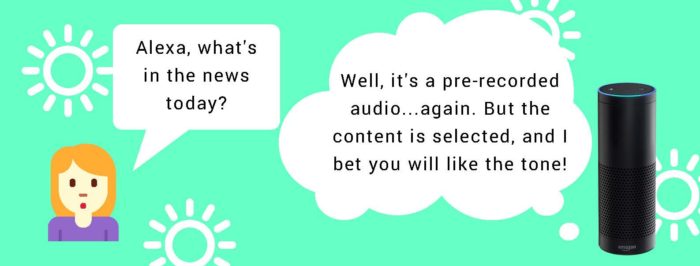

Many newsrooms have adapted content for the new interface, creating “flash-briefings” for Alexa (or “actions” for Google’s Assistant), but the largest legacy news organizations have pursued predictable agendas. CNN’s briefing lasts five minutes, while The New York Times’ clocks in at 15 minutes. The Wall Street Journal offers several skills dedicated to different formats and topics, including a minute briefing, tech news, and financial stories, while NPR integrates two feeds under one skill—users can choose NPR’s hourly news update or the Business Story of the Day. Yet, regardless of how newsrooms try to spice up their flash-briefings, they have failed to think beyond the existing broadcast model and must ask themselves a critical question: How are their flash-briefings different from listening to an anchor reading on the radio?

Nicely done: BuzzFeed, Hearst

One big challenge is to distinguish an already defined brand on the new platform. BuzzFeed tries to offer a unique selection of news, in keeping with the offbeat and varied content on its website: Aside from addressing the biggest news stories of the day, BuzzFeed also includes casual lifestyle pieces on such topics as candy corn recipes for Halloween. Hearst, meanwhile, not only creates flash-briefings for its large and small newspapers—it’s also launched a series of interactive skills for its magazines that go beyond basic flash-briefing. You may ask Good Housekeeping for a weeknight dinner suggestion, for example, or instructions on how to remove an oil stain from fabric. You can hear an excerpt from Oprah Winfrey’s best-selling book What I Know for Sure, courtesy of O, The Oprah Magazine.

Thinking outside the box: The Washington Post, Quartz

While most newsrooms rely on straightforward flash-briefing skills, two publications stand out. One, perhaps unsurprisingly, is The Washington Post, which was purchased by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos several years ago. The Post deploys a “notification” to alert Amazon Echo users whenever a new story is posted. Quartz uses a similar flash-briefing skill as most other publications, but instead of pre-recording the headlines, Quartz creates two reporting bots, Brian and Kendra, that can automatically broadcast the first five stories on its mobile app. These innovations enable The Washington Post and Quartz to update their news content instead of releasing only one news summary per day.

Creating a voice interface skill is easier than you think

Building a “skill” on Amazon Echo or an “action” on Google Home can be done by journalists and other media professionals who have no experience in writing code.

For Alexa, go to Amazon Developer and sign up for an account. You will get detailed guidelines for the Alexa Skills Kit. If you find that too complicated. just search for “how to create an Alexa skill” on YouTube, and you will see more than 180,000 results, including a playlist with six “how-to” videos by Amazon. There also are step-by-step tutorials created by the technology research and development firm Dabble Lab, including one for building an Alexa skill in 11 minutes.

The process will be even simpler if you know how to use the bot-builder Dexter. John Keefe, the product manager at Quartz, exclaimed that with Dexter’s new feature “making an Alexa skill just got ridiculously easy.” Storyline, an Alexa skill builder founded by Vasili Shynkarenka and Maxim Abramchuck, provides a coding-free design experience for people who don’t know much about programming, allowing them to focus more on designing meaningful interactions.

Knowing how to build a voice interface skill is the easy part. It’s much more important to build an effective and sustainable news product.

How could voice interface improve the news experience?

|

Interactive: “Alexa, can you tell me more about that story?” You hear something that interests you, but you aren’t able to let Alexa know that. It’s less interactive than using our smartphones—at least we can click on the headline and read the full article. |

|

Personalized: “Hi Renee, here’s your news on Studio 20.” At this point, we can choose the news source we like, but we can’t choose the type of news we like. |

|

Compatible with other devices: “Hey Renee, check your phone! I just sent you a story on Studio 20.” If you don’t have the time to hear an entire story, what if your smart speaker could send the article to your phone? |

|

Human-like tones:Speaking as a friend, not an anchor. Your smart voice assistant acts like an intimate friend, not an emotionless anchor. It’s important for newsrooms to decide what kind of tone they want. The most common method is to record an anchor or an audio producer, or to use the default voice from Amazon or Google, but IBM’s newly launched Watson Assistant allows companies to play with the tone, speed, and volume. So stay tuned for a warmer, emerging voice technology! |

Challenges and controversies

|

Advanced machine learning How to make the “talking robot” accurately respond to various questions and follow-ups from the user? |

|

Manpower Do you have enough people in your team working on voice interface? |

|

Monitoring User Engagement and Impact How do you measure users’ reactions? How do you measure impact or success? |

|

Monetization How can you make money from voice interface? |

|

Privacy Is that smart speaker eavesdropping? |

|

Customers What if I don’t want to talk to a robot? |

Key quotes

How do we maintain a sense of usefulness and playfulness that brings people back to use these interfaces? That’s really key.

These devices have been deliberately designed to make you anthropomorphize them. You try to please them—you don’t do that to newspapers. If you get the news from Alexa, you get it in Alexa’s voice and not in The Washington Post’s voice or Fox News’ voice.

Why is this important?

It’s predicted that by 2020 more than 100 million smart speakers will have been sold, making smart voice interface the next major platform that the news industry dares not neglect.Killer links

- Nieman Lab The future of news is humans talking to machines

- Nieman Lab Writing answers before you know the question

- Nieman Reports AI Is Journalism’s Next Big Threat (or Opportunity)

- Associated Press Report: How artificial intelligence will impact journalism

- Digiday BBC has made a drama for Amazon Echo and Google Home

- NPR and Edison Research The Smart Audio Report

People to follow

-

John Keefe is a bot developer and product manager for Quartz.

John Keefe is a bot developer and product manager for Quartz. -

Alex Sujong Laughlin is an audio producer at Buzzfeed.

Alex Sujong Laughlin is an audio producer at Buzzfeed. -

Trushar Barot is apps editor for BBC World and digital launch editor for the BBC’s new Indian-language service, based in Delhi.

Trushar Barot is apps editor for BBC World and digital launch editor for the BBC’s new Indian-language service, based in Delhi.