Deep in rural Nebraska sits a meatpacking plant, where workers stand shoulder to shoulder for hours at a time. In the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, plant workers pack into windowless rooms for their lunch breaks, where they cannot wear masks while eating.

A recent federal lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union documented how, in the absence of proper oversight, unsafe working conditions throughout the Nebraskan meatpacking industry created a breeding ground for Covid-19 infection. The lawsuit alleges that plants failed to take basic measures to protect their workers, such as adequate masks provision and Covid-19 testing. “It’s a terrible cycle,” says Albert Maribaga, a South Sudanese community leader, and employment specialist at the Catholic Social Services of Nebraska, “young men go to work at these plants, get sick and don’t know it, and come home and infect their families.”

Throughout the Covid-19 pandemic, the South Sudanese immigrant community of Nebraska has been hit hard, trapped in poor working conditions due to an uncertain economy. Nebraska is home to one of the largest enclaves of South Sudanese immigrants in the United States, with an estimated 10,000 residents in Omaha alone. According to researchers University of Nebraska Omaha, the population of South Sudanese residents in Nebraska is small enough that its value is not publicly available, by the United States Census Bureau. This redaction indicates that the Nebraskan South Sudanese population falls between 10,000 and 65,000 residents. The population of Black or African American residents in Nebraska is 100590 as of 2019, South Sudanese Nebraskans may account for anywhere between 10%-64.5% of that sub-population.

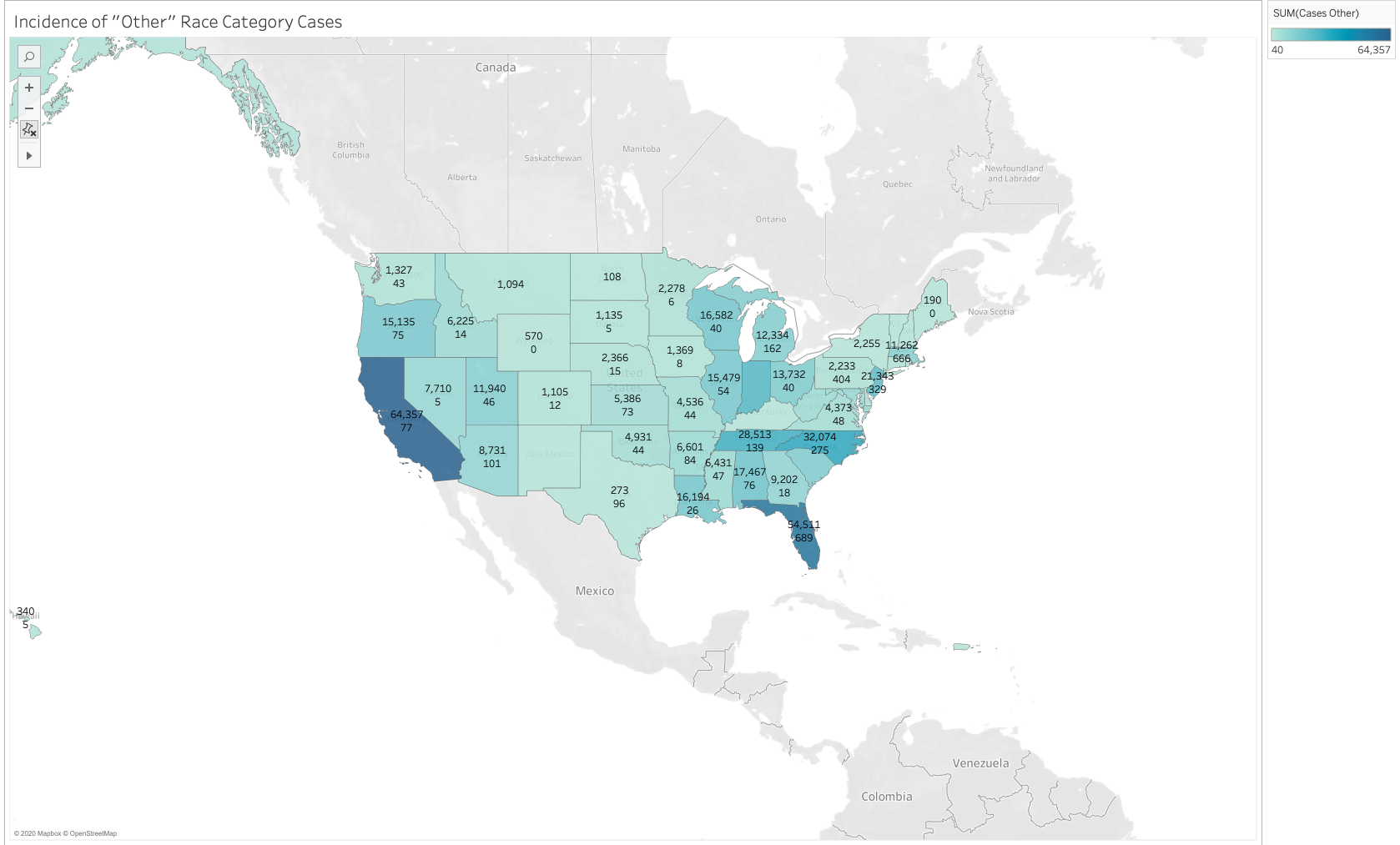

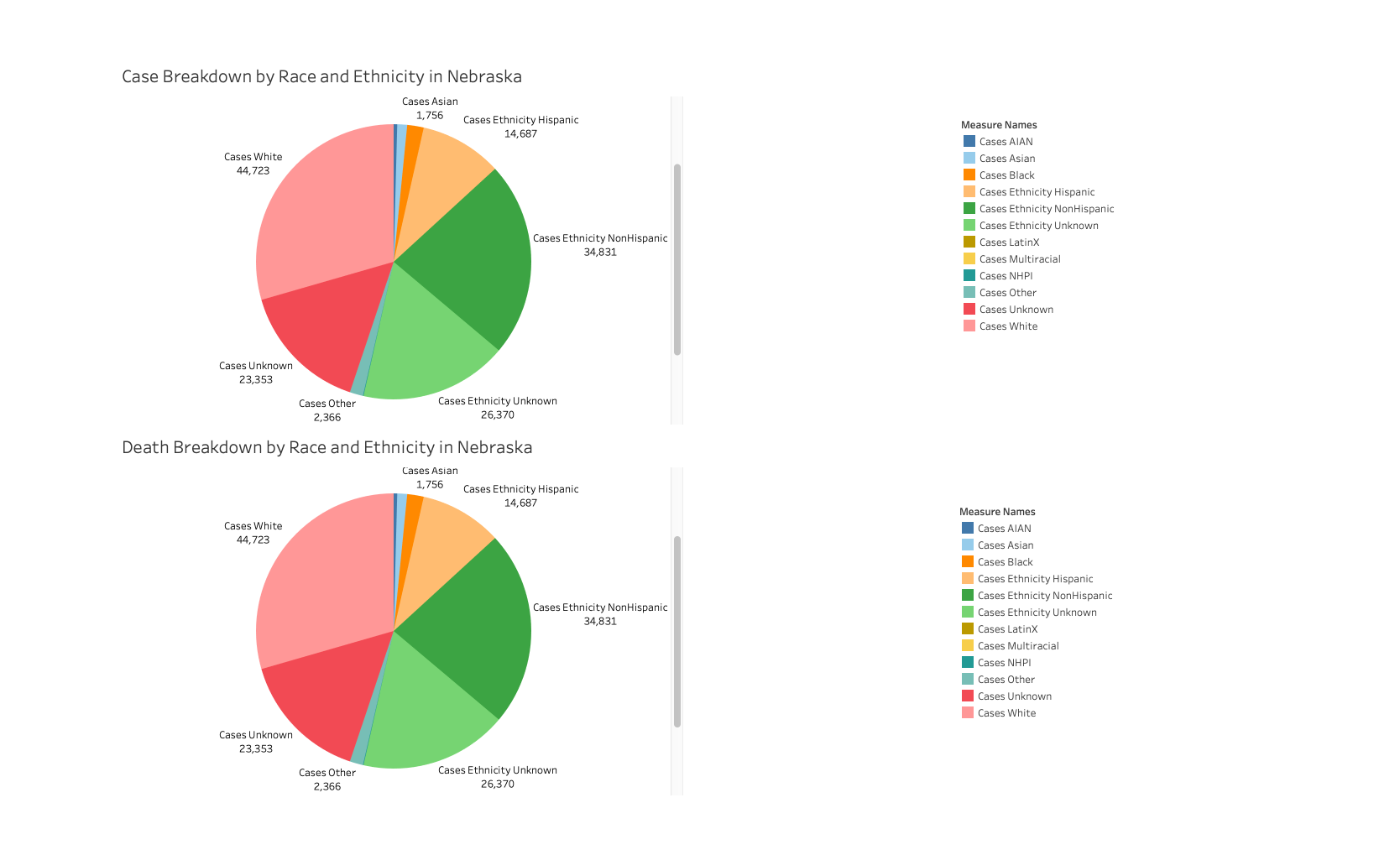

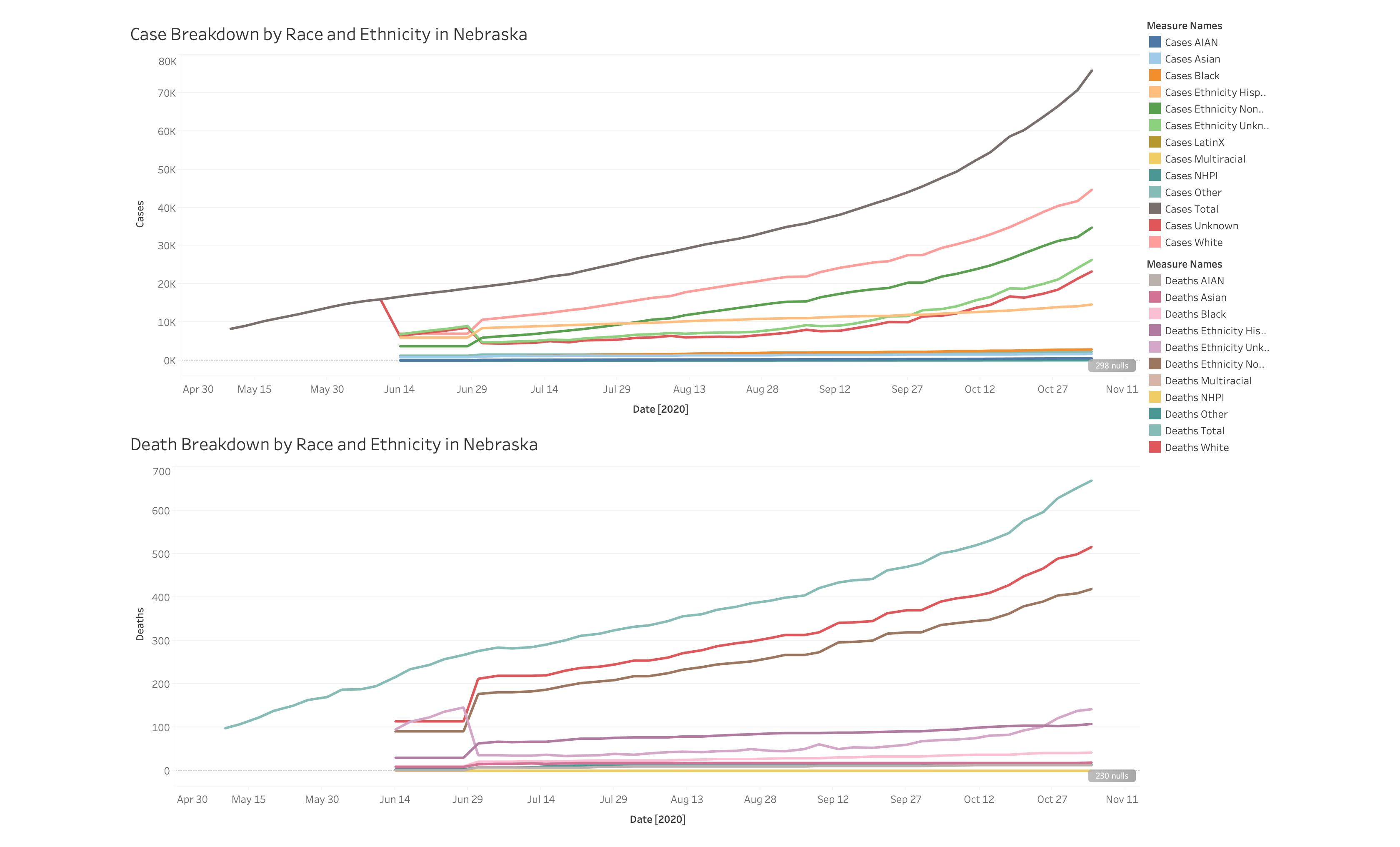

Data from The Atlantic’s Covid Tracking Project reveals that Black or African American Nebraskans account for 5% of the state’s Covid-19 cases, and 6% of their Covid-19 deaths. The accuracy of Nebraska’s Covid-19 race data reporting is suspect, as state officials have only disclosed race data for 50% of cases, and 62% of deaths. In the graph below, we see that of Nebraska’s minority communities Black or African Americans (represented in turquoise) had the highest Covid-19 case rates, as of December 9th, 2020. It should be noted that Nebraska does not report Covid-19 rates for the LatinX community.

Organizations like the Catholic Social Services of Nebraska, and the Lutheran Family Services of Nebraska help place South Sudanese immigrants in jobs throughout the state. This is not an easy task, as 79.3% of South Sudanese immigrants come to America with a high school level education or less. The Nebraska Office of Health Disparities and Health Equities reports 52.7% of homes that speak African languages speak English less than “very well”. “Because of the pandemic, all job interviews are over the phone,” says Maribaga “translators are not allowed in phone interviews”. With these limitations, South Sudanese community members often are limited to work in meatpacking warehouses, nursing homes, and as housekeepers – all high-risk jobs in the Covid-19 pandemic.

Prior to, and throughout the pandemic, the Trump administration has pursued an aggressive deregulatory agenda, reducing safety standards for industrial and service workers. In 2017, the Trump administration halted electronic reporting of workplace injury and illness reports by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. In June 2018, Trump’s Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services halved fines for nursing homes violating safe working condition practices. Although the federal government was pressured to require greater transparency from nursing homes regarding Covid-19 outbreaks in May 2020, these facilities are not required to inform staff members about case rates in their facilities.

But it is the conditions in the Nebraskan meatpacking facilities, such as the Smithfield Foods warehouse in Crete, and Noah’s Ark processing plant in Hastings, that have been the source of countless Covid-19 cases, and deaths. In February 2018, the Trump administration revised inspection standards for the Federal Food Safety and Inspection Service, reducing government oversight of safety measures in meatpacking warehouses with the intent to increase food production speeds.

South Sudanese meatpacking workers have relied on their employers’ healthcare plans to protect them and their families during the pandemic, all too often these healthcare plans are insufficient. Albert Maribaga reports new meatpacking workers find themselves without coverage, if their healthcare deductibles go unmet. Maribaga also notes that long term hospital care is not covered in meatpacking healthcare plans. Workers infected with Covid-19 are forced to stay home without pay, with no room in their budget to seek the extended treatment necessary to deal with severe symptoms. Christa Yoakum, Senior Welcoming Coordinator for Nebraska Appleseed’s Immigrants & Communities Program, alluded to another issue with meatpacking healthcare: “many plans are not accepted by local hospitals, and in-network hospitals are too far away to access”. Undocumented South Sudanese Nebraskans are unlikely to seek treatment altogether, as they are without social security numbers.

The Nebraskan South Sudanese community faces socioeconomic factors, outside of poor working conditions, that contribute to the spread and fatalities of Covid-19. Approximately 1 in 3 Black, non-Hispanic Nebraskans live in poverty. According to Christa Yoakum: “if workers don’t get Covid in the factory, they get it while carpooling to and from the factory because they cannot afford individual transportation”. Yoakum also points out, that often times both parents in immigrant households get infected with Covid-19, because both work in the same facility.

Cezar Garcia, a Community Organizer for Nebraska Appleseed’s Immigrants & Communities Program, highlights how community dynamics, brought on by economic stress, contributes to the spread of Covid-19 in the South Sudanese community: “often times meatpacking workers aren’t just providing for their immediate family, they support their extended family too”. Sole providers for households or extended networks face pressure to show up for work regardless of health risks, even if they test positive for Covid-19. It is common in these communities for older members to live with their families, because they cannot afford housing in assisted living centers. While younger family members with more robust immune systems can fight off the symptoms of Covid-19, elders perish. At the time of our interview, Albert Maribaga knew of five community elders who had passed away that week.

Some Nebraskan institutions are developing programs to help their immigrant communities, centered around inclusion, employment, and awareness. In South Sioux City, newscasters have been broadcasting public service announcements about Covid-19 in the different languages of Nebraska’s immigrant communities. “These awareness initiatives are so important,” says Cezar Garcia, “I have heard stories about people who don’t know when or how to wear their masks, and they’ve been relying on the news to get that information”. Food banks across Nebraska have adjusted their models for food delivery, opting to subsidize restaurants and grocery stores that serve foods from immigrant’s home countries. Christa Yoakum has confirmed that an anonymous donor has financed an angel fund to help pay for the treatment of Covid-19 infected undocumented workers. The Worldwide Education Services have doubled down on its existing proposals to Nebraska’s state senate lobbying for the certification of immigrant practitioners who hold medical licenses in their home countries to be certified as registered nurses and vaccine administrants.

The road to commensurate support for South Sudanese immigrants in Nebraska is long, but the Covid-19 pandemic has brought them unprecedented connection to non-for-profits. “Nebraska is a big state, we have relied on volunteers and word of mouth to build connections to immigrant communities,” says Yoakum “now, we have direct communication with community members, and we will strengthen and deepen our ties with them to provide long term support.”