Hope in the war on lies

Junk news will never go away, but technology and media companies can both take steps to check the spread of falsehoods.

Let’s begin by facing one fact: Fake news has a long history.

This makes fake news a wicked problem that will never go away. Fake news includes all kinds of falsehoods delivered as facts, from the crafty disinformation of political propaganda to the sensational hoaxes and rumor-mongering of yellow journalism.

The Internet has facilitated the spread of fake news, as bad actors can easily disseminate false stories online, even sharing major social media platforms—such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube—with the most trusted newsrooms. As long as there is a demand to feed biases, and often money to be made, the bad actors will not stop.

The situation has grown so grim that the term “fake news” now gets regularly used to discredit genuine reporting.

Yet the destructive effects of junk news can be mitigated. With fact-checkers and evermore-sophisticated technology, companies like Facebook and Google can play a major role in curbing the spread of fake news, but they can’t do it alone.

A multi-pronged approach is needed to battle the problem.

What is fake news?

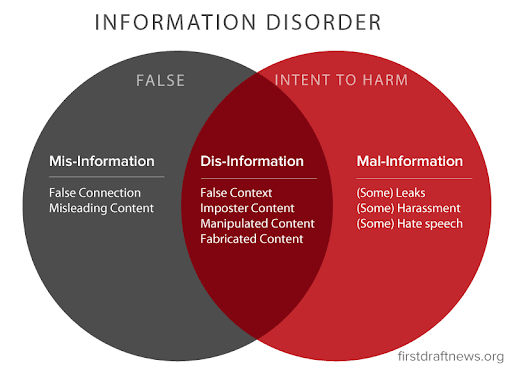

The nonprofit First Draft News came up with this Venn diagram to show how fake news is not simply false—it can be deliberately weaponized to inflict harm.

While the methods of disseminating fake news are more sophisticated and far-reaching today, the political motivations have remained the same: Shaping public opinion to influence events and lead to desired outcomes.

Around 33 BC, before Octavian became the Roman Emperor Augustus, he had slogans etched onto coins to paint his rival Mark Antony as a womanizer and a drunkard who had become a puppet of the Egyptian queen Cleopatra.

Nearly two millennia later, newspaper baron William Randolph Hearst used the sinking of a U.S. battleship in Havana Harbor to publish stories, without evidence, that pushed America to declare war on Spain.

Newspapers had already learned that hoaxes boosted circulation. In 1835, the New York Sun famously saw a boom in its readership when it published a series of six bogus stories about the discovery of life on the moon.

But the phrase “fake news” was not widely used until just a few years ago. Journalist Sharyl Attkisson pins the term’s birth to 2016, when First Draft News announced its program to tackle “malicious hoaxes and fake news reports.”

Noting the group had received funding from Google and George Soros’ Open Society Foundations, Atkisson concluded political liberals had coined the phrase to discredit conservative news outlets. Since then, however, some of the biggest users of the term “fake news” have been conservative politicians, led by U.S. President Donald Trump, who has deployed the label to dismiss unfavorable news as dishonest.

In his first year in office, Trump had tweeted or retweeted posts about “fake news” or “fake media” 166 times. Among his favorite targets in the “Fake News Media” remain the “Failing New York Times” and “Fake News CNN.”

Disinformation comes from both conservatives and liberals, but fake political news in America is mostly a right-wing phenomenon, according to a study last year tracking the use of social media in the U.S. for the University of Oxford’s Internet Institute.

In the three months before Trump’s first State of the Union Address in 2018, researchers observed “a network of Trump supporters” on Twitter sharing “the widest range of known junk news sources” and circulating “more junk news than all the other groups put together.”

On Facebook, “extreme hard right pages” —distinct from pages supporting the Republican Party—were the biggest sharers of fake news. A later report on social media before the 2018 midterm elections found the influence of these fake news purveyors growing: “[J]unk news once consumed by President Trump’s support base and the far-right is now being consumed by more mainstream conservative social media users.”

Blaming the Internet

The 2016 election shined a spotlight on the role of technology in creating and spreading fake news. But simply blaming the Internet has been a bit like trying to hold back an ocean with one’s hands.

Ten years before fake news was credited with electing a U.S president, New York University professor Jay Rosen was looking at the ways in which technology and the Internet were turning passive consumers into content producers and programmers. In “The People Formerly Known as the Audience,” Rosen put professional “media people” on notice, pointing to “a shift in power” that would inevitably happen in the new media ecosystem.

With the rise of social media, the power shift has become more pronounced. Platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube allow the people formerly known as the audience to not only choose when, where, and how to engage with media but to create their own content from the comfort of their bedrooms and reach millions of other users.

Rather than lamenting lost days, newsrooms need to deal with these active users, a public that is, Rosen wrote, “more able, less predictable.”

Forget deepfakes: Misinformation is showing up in our most personal online spaces. https://t.co/Cbfbqw6p9w @cward1e #predix2019

— Nieman Lab (@NiemanLab) December 12, 2018

The bad actors

Social platforms let users post content without the traditional hurdles and oversight that stopped most publishers from spreading fake news. A bad actor can exploit anonymity, cheap access, and a lack of filters to easily propagate falsehoods, even employing automated bots to post continuously and hashtags to reach more people.

With such low barriers to entry, the bad actors have run the gamut from state-sponsored pushers of political agendas to people who just want to make a quick buck.

Reacting to criticism over its role in the circulation of fake news during the 2016 U.S. election, Facebook announced a program to “stop misinformation” on its platform, stressing that financially motivated “spammers” were at the center of the fake-news problem: “These spammers make money by masquerading as legitimate news publishers and posting hoaxes that get people to visit their sites, which are mostly ads.”

While Facebook promised to remove the “economic incentives” from the spammers, critics pointed out that the company had provided the platform and even profited from the ads of political and state-sponsored fakers.

BuzzFeed reported that, in the final months of the 2016 U.S. election, fake news stories were more often shared on Facebook than the work of established newsrooms. Another study last year by three MIT scholars found fake news traveled much faster and farther than real news on Twitter.

Last summer Facebook deactivated the page of USA Really, a Moscow-based site linked to the Russian government. USA Really says its mission is to “Wake Up Americans” by promoting “crucial information and problems, which are hushed up by the conventional American media controlled by the establishment and oligarchy of the United States.” On one day in March, the site’s top story was typically inflammatory: “Is War Necessary to End Abortion in the States?”

State-backed players have sent divisive messages through Facebook. Myanmar’s military used the platform to spread propaganda and false stories about the Rohingya, sparking widespread violence against the ethnic minority, including murders, rapes, and the forced migration of more than 700,000 people.

But Facebook isn’t the only social media platform that has spread malicious viral posts. Fake news passed on WhatsApp about child abductions, for example, led to a series of lynchings and other mob violence in India and Mexico.

The impact of small players, often just individuals, has been noteworthy, as the power of the social web has turned some fringe operators into consequential voices with websites and social media groups sharing stories tailored to fit their ideologies.

For 20 years Alex Jones promoted conspiracy theories on the radio and public-access television. Now he reaches nearly 2.5 million people monthly on his InfoWars website. InfoWars has promoted conspiracy theories that put the U.S. government at the root of problems and catastrophes, including the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the mass shooting at the Sandy Hook Elementary School.

Like USA Really, InfoWars claims it’s offering untold news the mainstream media won’t touch. Last summer, Facebook and YouTube barred Jones and InfoWars for promoting hate speech and violence, though Jones’ videos can still be found on both platforms.

Their politics aside, most of these traffickers in fake news want to make money. The audience for InfoWars is overwhelmingly American and male older than 45, and Jones has reaped substantial financial rewards from hawking merchandise to them, from T-shirts to overpriced health supplements. In the months before the 2016 U.S. presidential election, more than 100 pro-Trump websites were set up by teenagers in one small town in Macedonia.

The teenagers were not generally Trump supporters, but by posting bogus news on Facebook, they drove visitors to their sites and earned thousands of dollars from Internet ads..

Christopher Blair’s Facebook page, “America’s Last Line of Defense,” mocks the sensationalism of this kind of far-fetched political news as “conservative fan fiction.” His parodies are marked “satire” and carry the disclaimer, “Nothing on this page is real.” But America’s Last Line of Defense nevertheless became one of Facebook’s most popular pages among Trump-supporting conservatives over the age of 55.

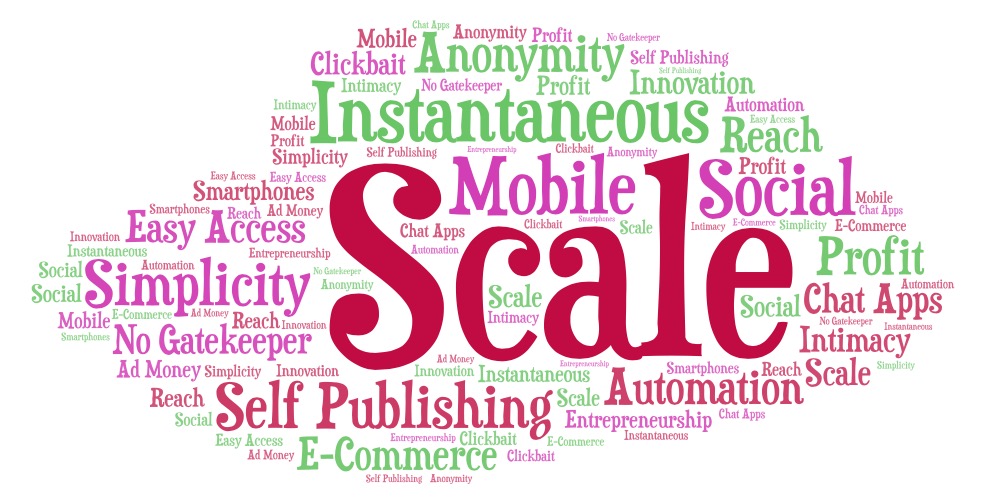

20 reasons why the Internet makes fake news so prevalent

The consumers

A Washington Post profile of Blair featured one of his unexpected fans, Shirley Chapian, a 76-year-old retiree in Nevada whose daily news diet consisted of posts from Facebook pages with such titles as “Trump 2020,” “Free Speech Patriots,” and “Taking Back America.”

Nationalism has been a driving force behind a lot of fake news, not only in the United States but in other countries, according to a recent report by the BBC on social media and fake news in India, Kenya, and Nigeria.

The consumers of fake news tended to have extreme views on politics, religion, and ethnicity, and they shared bogus stories out of a desire to reinforce their views and to strengthen their sense of national identity.

The quality of the source didn’t matter. They distrusted the mainstream media for not reflecting their prejudices. Studies have found that fake news consumers tend to be less media literate than the general population and they mostly come from two age groups, between the ages of 18 to 35 and older people who are on social media. Their lack of media literacy was a key reason why they shared dubious “insider information” missing from the mainstream.

Psychologists explain their demand for fake content as a result of confirmation bias, a condition that finds people seeking out information that aligns with their beliefs.

Chapian, for example, had always voted Republican and had reservations about Barack Obama. On Facebook, she read stories about Obama that were false but confirmed her bias: He was a socialist and inexperienced, the bogus stories claimed, and he had faked his college transcripts and birth certificate.

Chapian didn’t care that the network TV news had not reported any of these stories. The problem with fake news in the modern age is that confirmation bias forms a circle of reinforcement: The fake news is produced and shared by people with the same opinions and prejudices, creating the perfect storm.

Not giving in to fake news

But leaving fake news to flourish on the web is not an option. Fake news leads to confusion, stokes unfounded fears, polarizes societies, and erodes trust in democratic institutions and the free press.

In politics, fake news has exerted influence over presidential elections in the U.S. and Brazil, as well as in the UK’s Brexit referendum. On the ground, fake news has fueled hate, vigilantism, and ethnic violence.

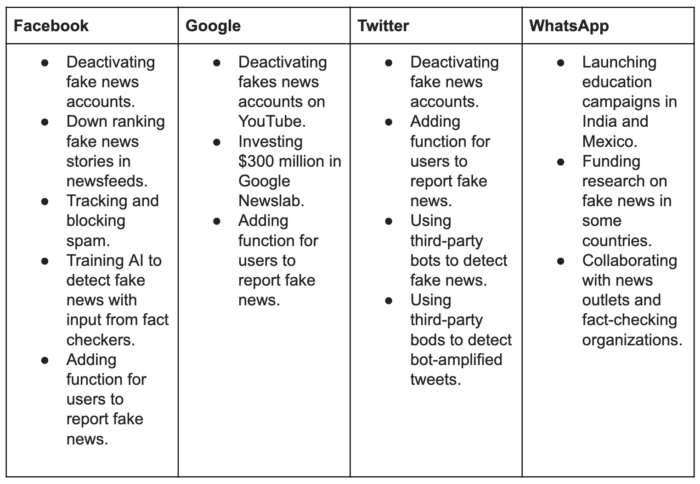

In response to widespread criticism for their roles in allowing fake news to proliferate, technology firms and social media platforms have joined a multifaceted effort to fight fake news, introducing measures to mitigate falsehoods through fact checking, to educate the public in media literacy, and to intervene on platforms to down rank suspect stories.

Facebook, for example, has been blocking fake-news publications from running pages, though some organizations classified as hate groups have retained their pages, despite a recent ban on posts supporting white nationalists and separatists.

In addition, Facebook is allowing users to report questionable posts, and it’s applying machine learning to the work of fact checkers to refine its ability to detect false content and bad actors. Right now, there are about 30 organizations in about 20 countries that work with Facebook to fact-check stories.

Twitter is using bots, like Fatima, to search for tweets linked to discredited stories, and it has employed two tools developed by computer scientists at the University of Indiana, Hoaxley and Botometer, to detect bots spreading fake news on the platform. Browser extensions like Botcheck help users identify tweets amplified by bots.

NewsGuard was launched last year by journalist Steven Brill and former Wall Street Journal publisher L. Gordon Crovitz, after raising $6 million from investors, including the Knight Foundation and the French advertising and public relations firm Publicis.

The start-up employs seasoned journalists to review content and score news sites on their reliability. It recently introduced a browser extension that shows a green flag for a trusted website and a red flag for a questionable source.

Efforts by technology companies

Media literacy programs and legislation

Universities, research institutes, and other nonprofit organizations are fighting fake news through education, creating an awareness of the problem and teaching people how to identify fake news. Some groups, like the News Literacy Project, work directly with schools. The University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Public Policy Center, on the other hand, runs the nonpartisan site FactCheck.org and offers free resources for civics classrooms, including multimedia curriculum aids such as games and quizzes.

Many countries are looking at legislation to tackle the problem. For example, Ireland is considering a bill to prohibit the use of bots to create 25 or more personas on social media with the goal of influencing political debate.

Last July, Egypt passed a law to treat social media accounts and blogs with more than 5,000 followers as media outlets that can be prosecuted for publishing false news or inciting others to break the law.

Some civil libertarians hold that similar legislative fixes in the U.S. could violate constitutional protections against censorship by the government, but the First Amendment also guarantees the right to open discourse and reasoned debate, which fake news is undermining.

Free speech protections can’t stop the companies themselves from removing rule-breakers from the privately owned forums. If the tech firms can’t do a better job of keeping fake news off their platforms, they run the risk of more intensive government intervention.

One fight, different interests

Yet a lack of coordination among the stakeholders in this war against fake news—the social-media platforms and tech companies, the news outlets and governments—reveals “mixed motives” and conflicting interests, according to a report by the London School of Economics. Consequently, the remedies so far have remained isolated and piecemeal, yielding “uncertain” results: ”The digital platforms, news organizations, political campaigners and civil society all need to be part of a new integrated policy arrangement.”

The good news

- Facebook shut down 583 million fake accounts and removed 2.5 million postings of hate speech in the first three months of last year alone.

- Twitter removed 70 million accounts last May and June.

- Facebook staffed a “War Room” to combat fake news ahead of last year’s U.S. midterm elections.

- Facebook changed its algorithm to prioritize posts from friends, reducing the visibility of fake news on its feeds.

The bad news

- Trump is making more false and misleading claims. In his first 100 days as president, he made an average of 4.9 such claims a day. In 2018, his daily average tripled, hitting 15 false or misleading claims a day, reported the Washington Post. Over just the final month before last year’s midterm election, Trump said 1,104 things that were false or partially untrue. In one day alone—when he traveled to Texas for a campaign rally in support of Sen. Ted Cruz—Trump made 83 untrue claims.

- While Facebook, Google, and Twitter have taken steps to combat fake news, critics complain the companies have been slow to accept responsibility for what gets on their platforms. The New York Times reported that Facebook ignored warnings that its platform was becoming a tool for government propaganda and ethnic cleansing. Facebook knew about the Russian influence campaign before the 2016 U.S. elections but did nothing to address it.

- Laws to stop the flow of fake news are being used to silence government critics. For example, Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte targeted journalist Maria Ressa after she co-founded the news site Rappler. When an attempt to revoke Rappler’s license was unsuccessful, Ressa was sued by a prominent Filipino businessman for “cyber-libel,” under a new law that was passed four months after the offending story had been published.

- Deep fakes are still difficult to spot, and technology will likely make them easier to produce and more realistic.

Quick ways to spot fake content

- First impressions count. Does the website look professionally done? Note the language, and look out for glaring factual or grammatical mistakes. Does the article cite reliable sources? Does the site have dubious ads?

- Check out the validity of the information. Has the news been reported by other publications?

- Use tools like Google Reverse Image and TinEye to verify images.

- Consult websites that regularly pick out fake news, like Snopes, FactCheck.org, PolitiFact, and Poynter.

- Click for information on the sourced website using the “i” button on Facebook and YouTube.

- Use a tool like NewsGuard.

- Be skeptical about memes. They’re quick and opinionated—and meant to go viral.

- If you spot something, flag it. Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube have report or flag functions on each post.

Now what?

If history’s a guide, the demand for fake news will never dry up. The supply, however, can be reduced, and this is where the technology companies can play a big part.

By banning the propagators of fake news from having social media accounts, or reducing the visibility of their posts, tech companies can significantly cut the supply of misinformation.

Social media bans will result in falling readership for fake news sites, and fewer readers will bring drops in ad revenue, thereby removing a big incentive for producing fake news. Some have called for programmatic advertising companies to stop placing ads on fake news sites.

The major social media companies know other steps they can take to better tackle fake news, but they remain reluctant to play more active roles, insisting they only provide neutral platforms—they’re not publishers.

Yet the companies are already acting as referees, as evidenced by the recent decision of Facebook and YouTube to begin cracking down on misinformation that can cause “real-word harm” (in Facebook’s words). In February, for example, YouTube announced it would prevent all ads from appearing on videos spreading anti-vaccine propaganda.

Now these companies must more closely police their platforms, according to a new report by NYU’s Stern Center for Business and Human Rights. This report urges the companies to hire content officers and fact-checkers, to more quickly remove fake news posts and expunge bot networks, to more clearly state their rules and to provide robust appeals processes to remedy erroneous takedowns, and to even support “narrow, targeted” government regulation.

The long-term interests of the social media platforms would be best served by becoming more trustworthy news sources and by more fully participating in proposed fixes for the fake news problem.

Much has been said about the way fake news has reinforced a lack of trust in the free press, but this situation may be changing. According to its annual “trust barometer,” the public relations firm Edelman found news engagement on the upswing and traditional publishers had become the most trusted sources of information in the U.S., Canada, and Europe.

This year 65 percent of respondents said they believed the news on traditional media, twice the number that trusted social media; 73 percent said they worried about “fake news.” As more newsrooms have stressed opinions as a way to generate excitement and capture audiences, their customers appear to desire greater clarity.

An informed public will always be hungry for reliable sources of factual information, making genuine reporting the best way to fight fake news.

Key quotes

“The use of propaganda is ancient, but never before has there been the technology to so effectively disseminate it, and rarely has the public mood been so febrile. If identifying lies and distortions was desirable before, isn’t it now essential self-defence?”

"While the media, platforms and public authorities are responding, there are challenges of coordination, a lack of research and information in policy-making, and the potential for conflicts of interest and disputes over media freedom, which are hindering necessary reforms."

Why is this important?

Fake news circulates misinformation and corrupts public debate.Killer links

- BBC The Godfather of Fake News

- The Guardian Trapped in a hoax: Survivors of conspiracy theories speak out

- The New York Times The Poison on Facebook and Twitter Is Still Spreading

- Knight Foundation Disinformation, ‘Fake News,’ and Influence Campaigns on Twitter

- Poynter Institute A guide to anti-misinformation actions around the world

- Facebook Working To Stop Misinformation and False News

People to follow

-

Craig Silverman is the media editor at BuzzFeed News.

Craig Silverman is the media editor at BuzzFeed News. -

Natalie Nougayrède writes a column for The Guardian.

-

Jamie Bartlett is a journalist and senior fellow at Demos.

Jamie Bartlett is a journalist and senior fellow at Demos. -

Daniel Funke covers fact-checking and misinformation for the Poynter Institute.

Daniel Funke covers fact-checking and misinformation for the Poynter Institute. -

Sara Fischer Is a media reporter at Axios.

Sara Fischer Is a media reporter at Axios. -

Alexios Mantzarlis is the founding director of the International Fact-Checking Network at the Poynter Institute.

Alexios Mantzarlis is the founding director of the International Fact-Checking Network at the Poynter Institute.