Satellites give newsrooms eyes in the sky

Satellite imagery has become an important tool to expose wrongdoings and to break news from anywhere.

Newsrooms are making a sophisticated addition to their toolboxes: Satellites orbiting the earth.

Satellite imagery has already helped journalists break big stories in hard-to-reach places. Recent examples include an exposé that found Botswana’s then-president Ian Khama building a large private compound on government land, with government funds and military labor, and the BBC Africa’s unmasking of three Cameroonian soldiers who executed two women and two young children. These scoops were made possible by the technology companies that launched shoebox-sized satellites, improving the cost and frequency of images. The visual data, however, comes with risks and limitations, and the lack of on-the-ground reporting raises the danger of misinterpreting images.

Using satellite imagery for news is not an easy task. It requires a third-party company to supply the images and an expert to help analyze them. Pierre Markuse, a satellite image processing expert, cautioned that journalists should ask “whether this third party might have an agenda of their own, which they are trying to push here.” Two American companies—Planet and DigitalGlobe—have played a particularly important role in making satellite imagery accessible to newsrooms. However, satellites are also governed by laws. The U.S. government, for instance, regulates satellite-operating companies under the Land Remote Sensing Policy Act of 1992, and other legislation in the U.S. and elsewhere has prohibited covering certain regions. When legislation is not enough, governments can simply buy exclusive rights to images. After 9/11, the U.S. government purchased the only commercially available high-resolution images of Afghanistan.

Yet despite these challenges and limitations, satellite imagery has become a powerful tool for reporters.

The View From Space

In 1960, the U.S. military launched its first spy satellite, Corona. Compared to satellite imagery today, the resolution was primitive, but for the first time the U.S. had genuine and current coverage of the Soviet Union, China, and other, previously denied areas from the Middle East to Southeast Asia. The public finally gained access to remote sensing in 1972, when NASA launched its Landsat 1 satellite. Before then, media organisations had to rely on declassified imagery. International news outlets began to use remote sensing more significantly after 1986, with the launch of the world’s first commercial satellite venture, the French SPOT (Satellite Pour l’Observation de la Terre). While Landsat 1 had delivered relatively low-resolution images that were too rough for commercial purposes—80 meters multispectral—SPOT recorded 10-meter resolution images.

When the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant exploded in what was then the Soviet Ukraine on April 26, 1986, SPOT had been in operation for only two months. Ten days after the incident, SPOT captured an image of the site. News agencies around the world used SPOT and Landsat images of the disaster region to show an out-of-control fire. With these images, the news media was able to challenge the Soviet Union’s claims about the severity of the accident.

The U.S. government allowed access to satellite imagery as long as national security wasn’t a concern. After the end of the Cold War, however, the U.S. permitted American companies to commercially operate earth observation satellites. In 1999, the Colorado-based company Space Imaging (now part of DigitalGlobe) launched Ikonos, then the world’s most powerful satellite. Ikonos offered high-quality imagery of up to 1 meter resolution.

Satellites are no longer big and bulky, and they don’t require years to manufacture. They can be as small as a cell phone SIM, making them cheaper, faster, and easier to launch. Today, nearly 1,900 satellites orbit the earth, and 300 of them were launched in 2017 alone.

Some satellites cover the earth several times a week. Planet’s satellites cover the earth every day. Better sensors have come with advancements in spatial resolution and measurement accuracies. DigitalGlobe’s WorldView series of satellites can capture images of the earth at a resolution of 30 centimeters. With a vastly improved space communication infrastructure, data downloads are faster, too.

Notable Stories

These technological developments have led to more journalistic projects using satellite imagery. For decades, satellite imagery helped to forecast the weather. Now journalists use the images to break stories, to verify information, and to cover war zones and the effects of climate change. Some of the best examples are mentioned below.

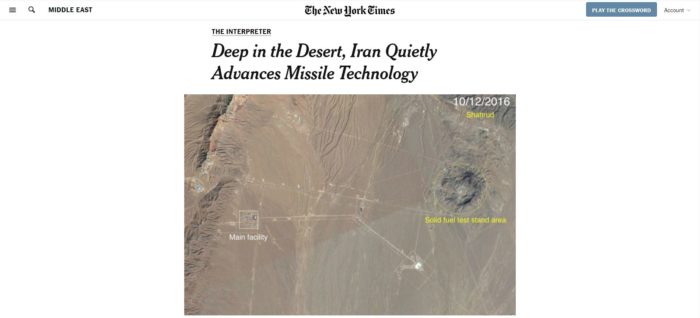

- Breaking news. “Deep in the Desert, Iran Quietly Advances Missile Technology,” The New York Times.

In 2018, the New York Times used satellite imagery from Planet to expose Iran’s secret long-range missile program. California-based weapons researchers came across clues showing that before his death the scientist Gen. Hassan Tehrani Moghaddam oversaw the construction of a secret missile facility in the remote Iranian desert. They picked through satellite photos of the facility and found the site focusing on advanced rocket engines and rocket fuel. The Times enlisted five outside experts to study new satellite imagery and to independently verify the researchers’ conclusions.

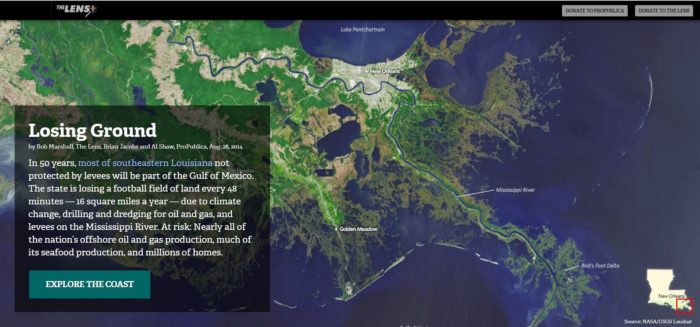

- Environmental investigations. “Losing Ground,” ProPublica and The Lens.

ProPublica and The Lens’ 2014 multimedia investigation into Louisiana’s coastal land loss used satellite imagery that showed nearly 2,000 square miles of coastal land in southeastern Louisiana had disappeared since 1922. Each year now, the investigation found, the state was shedding an additional 16 square miles to the Gulf of Mexico, due to climate change, oil and gas drilling, and river levees, endangering Louisiana’s energy and seafood industries as well as millions of homes.

- Tracking change. “Life in the camps,” Reuters.

Satellite imagery allowed Reuters to measure the exponential expansion of—and the growing humanitarian crisis in—Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh over just a few months.

- Factual verification. “Cameroon atrocity: Finding the soldiers who killed this woman,” BBC Africa.

In July 2018 a shocking video went viral on social media. It showed two women and two young children being led down a dirt road at gunpoint by a group of men dressed in camouflage. The women and children were blindfolded, forced to the ground, and shot at point-blank range. Social media posts claimed this scene took place in Cameroon, but the Cameroonian Government denied it, calling the video “fake news.” BBC Africa forensically analysed this video to discover where and when the scene unfolded and who were the perpetrators. The reporting team noticed a mountain range in the background and then went through years of satellite imagery to definitively determine that the killings took place in far northern Cameroon, where the army was fighting Boko Haram. The story named the village and several of the soldiers.

- Access to otherwise inaccessible areas. “Maps, Videos and Photos of the Explosions in China,” The New York Times.

When a chemical warehouse in Tianjin, China, exploded in 2015, the New York Times published satellite images of the disaster site. A follow-up report also used satellite imagery to show that the warehouse was only one of many that stored toxic chemicals near residential areas, violating Chinese safety regulations. The satellite images allowed the journalists to bypass the strictures Chinese authorities place on the media.

Look for Free

With the increasing number of satellites in space, many companies offer free images to media organisations, including:

- Sentinel Hub: Sentinel Hub’s Playground provides full-resolution Sentinel 2, Landsat 8, Digital Elevation Model (DEM) and MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) imagery.

- Earth Explorer: The Earth Explorer from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) mainly has U.S. images from Landsat satellites and NASA’s Land Data Products and Services.

- Copernicus: Copernicus is the European Union’s Earth Observation Programme, delivering near-real-time global data from six Sentinel satellites. Image resolution is better than that of Landsat.

- Google Earth: This mapping service catalogs satellite imagery, aerial photography, and geospatial datasets to offer 3D views of the earth.

- NASA Earthdata: The American space agency provides a wide array of satellite images along with other mapping and visualization tools. Users have access to a NASA and satellite data.

- Open Imagery Network.: The Open Imagery Network collects open-licensed imagery. Users can search and access the imagery through OpenAerialMap.

- ISRO: The Bhuvan Indian Geo Platform of ISRO is India’s national geo-portal, offering geospatial data and services, as well as tools for analysis.

Dangers of Misinterpretation

Journalists must be cautious when interpreting satellite images. In his report The Final Frontier: News Media’s Use of Commercial Satellite Imagery During War Time, U.S. Air Force Major Sean S. McKenna recalled that one of the American television networks had misinterpreted infrared images of the 1986 fire at the Chernobyl nuclear reactor, reporting that the blaze had rapidly spread beyond the plant simply because all of the surrounding vegetation appeared as red on the photograph.

Multiple factors can affect the way satellite images appear, said Pierre Markuse, in his guide for journalists using satellite imagery. Forests, for example, may look dark brown rather than the expected green, and some images have a blue tint due to atmospheric conditions scattering light. Markuse points out that the use of “atmospheric correction” can help reduce the impact of the atmosphere on image quality.

To avoid misinterpreting the data, journalists often seek the help of experts who can read the images. For instance, DigitalGlobe provides analysis of satellite imagery to media partners through its Maxar News Bureau. Stephen A. Wood, a senior analyst with Maxar, stressed that experts are geospatial authorities who have been trained to understand and interpret maps and satellite images. Wood noted an increasing number of journalists are developing imagery skills, but he said that publications are taking unnecessary risks by not bringing in experienced outsiders to verify their reporters’ interpretations. Markuse agrees, saying the only drawback to the technology is that images can easily be misinterpreted: “Lack of experience in interpreting [satellite images] could lead to false reporting.”

Misinterpretation almost tripped-up the Botswanan journalists who used satellite imagery to expose the construction of then-president Ian Khama’s luxury retreat. The reporters had been prevented from visiting the site, and Google Earth offered only images from 2006, 2010, and 2012. The last of these pictures showed a cluster of small homes occupied by Khama’s sister and two brothers. A new satellite image then revealed ongoing construction and a sprawling complex of 22 buildings with a private airstrip. But when the journalists tried to pick out details, they couldn’t distinguish a tower from an earth-moving machine, remembered Ntibinyane “Alvin” Ntibinyane, the co-founder of the nonprofit INK Center for Investigative Journalism. They enlisted a topographer with satellite imagery expertise to tell them when they were wrong. In an interview for a Reuters Institute paper on satellite journalism, Ntibinyane said that a careless mistake could have destroyed the credibility of an otherwise-accurate story. “If we’d gone with what we thought,” he said, “we would have messed the whole thing up.”

Some newsrooms, such as the New York Times, have hired in-house imagery experts, but even media organisations with fewer resources can find expertise. Here are some companies and nonprofits that will support reporting projects:

- Planet collects daily images of the entire earth’s landmass, and it provides images and expertise for media organisations.

- DigitalGlobe creates some of the highest resolution satellite images available, and they have partnered with news organisations, supplying images and the expertise to analyse them.

- Esri provides satellite imagery, analysis, and visualization tools that help journalists tell data-driven stories. It also provides resources to explore current and historic data from Landsat satellites.

- Descartes Labs is a service that collects data from public and commercial satellite imagery providers, including NASA and the European Space Agency.

- Radiant Earth Foundation aggregates the world’s open earth imagery and helps the global development community discover and analyze satellite imagery.

- EOS (Earth Observing System) helps to search and analyze imagery from most providers.

- ImageSat International obtains high-res satellite imagery and conducts data analysis.

- SkyTruth is an environmental group that uses satellite imagery to monitor natural resources.

Looking Forward

With improved technology, journalists are employing newer tools for news gathering, and satellite imagery is just another tool, said Martha Mendoza, an investigative reporter for the Associated Press. Mendoza was on the AP team that found the fishing industry in Southeast Asia employing slave labor. Satellite imagery of ship traffic helped to identify links in the slave fishing chain, and that allowed the reporters to then trace the seafood to supermarkets and pet food providers in the U.S. But the story ultimately required old-fashioned gumshoe reporting, Mendoza said. “[Satellites] are a really cool tool in storytelling, but they’re a tool just like a drone is a tool or . . . a new type of software for the database is a tool. It all enhances [the story], but at the end of the day you have to call people, go places, talk to people, be a news reporter.”

Mendoza’s comment highlights both the need for reporting skills and the limitations of satellite imagery. At present, satellite imagery alone cannot help journalists to identify individuals or to read the number off a car’s license plate. Most earth observation satellites use electro-optical imaging, so they cannot capture images through clouds and smoke. For this article, we tried getting satellite imagery of North Sentinel Island in the Bay of Bengal. The island is home to the Sentinelese people, who have remained virtually untouched by modern civilization. We hoped to capture last year’s fatal journey to the island by an American missionary, John Allen Chau. But the companies we reached out to didn’t have images because of cloud cover. We were searching for a needle in a haystack: What were the chances a satellite would be covering the spot where the news was breaking? We didn’t even get the opportunity to interpret an image.

Researchers are working on the use of machine learning to interpret satellite imagery, but until then, Wood said, journalists will have to rely on third-party companies for the imagery and analysis. Companies like Planet and DigitalGlobe sometimes provide satellite images to newsrooms in return for credit, which is valued for brand building, as their businesses depend on selling imagery to governments and private companies. One day, Markuse believes, some big media companies may orbit their own satellites, but the costs and needs of journalists more likely mean “that bigger media companies will have contracts with satellite image providers, and the smaller media entities will just buy images on demand when necessary.”

Key quotes

Journalists can most definitely read satellite images wrong. . . . I believe it to happen even more frequently now with easy access to satellite data.

When I opened [the satellite image], I was so surprised, I was like, ‘Wow, this is just bigger than I thought.

[Satellites] are a really cool tool in storytelling . . . but at the end of the day you have to call people, go places, talk to people, be a news reporter.

Why is this important?

Shoebox-sized satellites have increased access to topographic images, telling reporters about natural and man-made disasters, as well as about longer-term changes in the landscape. But reporters face the risks of misinterpretation and the hurdles of government controls.Killer links

People to follow

-

Malachy Browne works as a senior story producer at the New York Times, focusing on visual investigations.

Malachy Browne works as a senior story producer at the New York Times, focusing on visual investigations. -

Christiaan Triebert is a journalist specializing in open source investigations related to war and conflict.

Christiaan Triebert is a journalist specializing in open source investigations related to war and conflict. -

Pierre Markuse is a satellite image processing expert.

Pierre Markuse is a satellite image processing expert. -

Bellingcat is an international investigative journalism group.

Bellingcat is an international investigative journalism group.