Enough of bad news? Here’s a solution

Newsrooms increase reporting’s impact by giving audiences actual news they can use.

If you sometimes think the world is going to hell, you’re not alone. “I wake up in the morning, look at the paper, and shout, ‘Oh no!’” complains musician David Byrne, on his otherwise upbeat website, Reasons to Be Cheerful. “Often I’m depressed for half the day.”

Byrne speaks for most people. A 2018 survey by the American Psychological Association found that a majority of adults complained of “stress” from being exposed to news coverage of mass shootings, current politics, and climate change. While bad news may be fundamental in life, the negativity bias of newsrooms has been well established, and the idea that this might be a problem for the journalism business isn’t new. A decade ago the Associated Press published a white paper that found young audiences were disengaging from traditional news outlets due in part to “news fatigue.” Today social media perpetuates a cycle of negativity: One recent study discovered bad news on Twitter had a “significant effect” on the platform’s users, who reacted with anger and disgust, and other studies confirmed that Twitter was dominated by negative posters and negative tweets drew more attention than positive ones. No wonder new data from Ipsos Global @dvisor show that six in ten adults in 23 countries think their societies are broken. They express a lack of trust in institutions, especially in government, political parties, and the media.

A growing number of newsrooms are responding to this crisis of civic confidence by digging deeper into society’s troubles and then asking what can be done. “Constructive” or “solutions” journalism provides context and takes an evidence-based approach to examine remedies. Instead of building stories around conflicting sides, journalists look at responses to problems and ask whether these responses work. By this method, they can improve accountability while empowering audiences to act constructively. That doesn’t mean emphasizing positive or “happy” stories of people’s great intentions and altruistic motives. The focus of constructive journalism is on effectiveness, not good intentions. By accurately testing ideas against facts, solutions journalists can inform and remind readers that, despite our never-ending problems, some people are striving to make things better.

Over the last six years, the nonprofit Solutions Journalism Network has worked on constructive reporting projects with 156 news organizations. The projects sometimes brought together traditional competitors. For example, multiple newsrooms in New Mexico contributed to the series State of Change, which examined the challenges facing rural communities in the American West. Another, yearlong project had more than a dozen Philadelphia newsrooms collaborating to report on the challenges of reintegrating former inmates into society. The issues of re-entry and recidivism held special importance in Philadelphia, which had the highest per-capita incarceration rate of America’s biggest cities. Over the course of the project, more than 200 stories and four videos looked at life after prison, as well as the efficacy of existing efforts to help ex-inmates, various strategies to reform the unfairness of the bail bond system, and the special challenges faced by inmates with mental illness or mental disabilities. Philadelphia mayor Jim Kenny praised the stories for sparking a helpful discourse, showing the city how “to safely reduce our jail population and improve opportunities for those returning home.” The values and methods of solutions journalism elevated the issues, as journalists told the personal tales of “many people who were too long ignored,” Kenny said.

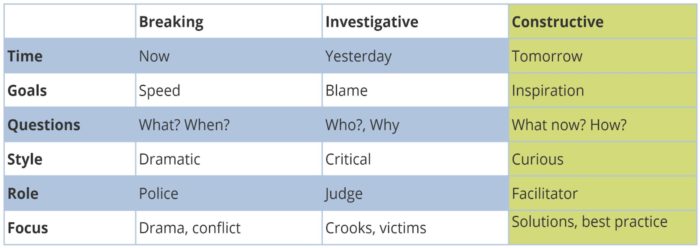

Groups like the the Solutions Journalism Network in the United States and the Constructive Institute in Denmark offer training and assistance for reporters and newsrooms. SJN was founded by David Bornstein, Courtney E. Martin, and Tina Rosenberg. All of them write for the New York Times’ “Fixes,” a blog created by Bornstein and Rosenberg to look at “solutions to social problems and why they work.” SJN curricula are used in 17 journalism schools, and the nonprofit keeps an online archive of more than 6,000 examples of constructive journalism from 160 countries. The vast majority of these stories are the products of a shift in common reporting practice—the adoption of a different mindset—and not the result of assistance from a mission-oriented journalism organization. The following chart compares the perspectives required for constructive or solutions journalism with the traditional approaches of breaking news and investigative reporting.

Source: The Constructive Institute

Solutions journalism doesn’t accentuate the positive.

Some outlets specialize in positive or feel-good news. The Good News Network, for instance, promotes “inspiring” content featuring doers of good deeds. It’s billed as “an antidote to the barrage of negativity experienced in the mainstream media.” If you’re looking for good news, you could talk to your Google Assistant—“Hey, Google, tell me something good”—and you’ll get a brief summary of similar news about problem solvers. But that’s not constructive journalism.

“Positive” journalism is not solutions journalism. The editors at Positive News say they’re “pioneers of ‘constructive journalism,’” yet their web magazine is less serious and less rigorous than constructive journalism. The stories are often about heroes and individual events that have little significance to society at large. They sometimes include consumer news. That doesn’t mean these stories are not useful or entertaining, but they’re not good examples of constructive journalism. Likewise, the term “transformative news” is sometimes used to mean solutions journalism. While transformative journalism takes a solutions-focused approach to covering the news, it has an element of feel-good news and prescriptive advocacy at the center of its practice.

To see how solutions journalism differs from the work of these outlets, consider the SF Homeless Project, an ongoing series of articles, radio pieces, and videos in various media outlets in the San Francisco Bay area. The stories tackled the issue of homelessness by breaking down the problem into component parts. The causes were diverse, as were the proposed solutions that reporters analyzed. How did one medical clinic find a way to more effectively treat opioid addiction, for example, and why were attempts to end tent cities by local governments so ineffective? Why were so many of the homeless young people, and did the state’s closure of mental health facilities contribute to homelessness?

Critics express skepticism about constructive journalism practices.

One of the criticisms leveled at constructive journalism is that it’s advocacy reporting promoting specific solutions. Some believe you can’t be both a “watchdog” and a solutions journalist.

But solutions journalism doesn’t spurn traditional watchdog reporting—it proposes to turn the watchdog lens on “what’s missing in today’s news: how people are responding to problems,” in the words of the Solutions Journalism Network. Typical reporting emphasizes the purely problematic side of issues, providing an incomplete and purely troublesome picture. Solutions journalism, on the other hand, posits that a fuller picture of societal problems will naturally end up grappling with what can be done about them.

Why does solutions journalism matter now?

As news outlets continue to struggle in the digital age, solutions journalism offers hope for healing news fatigue and reinstating trust in the press. According to the Solutions Journalism Network, it also makes good business sense.

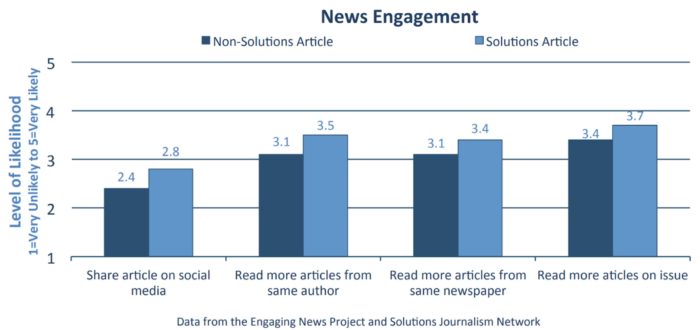

Solutions journalism drives audience engagement. Research reveals readers like stories about problems when they include possible solutions, and solutions-based articles left audiences feeling more satisfied, better informed, and more willing to share these stories with friends than other kinds of news. They were also more likely to return to the news outlet, and they felt more optimistic. In addition, solutions-oriented headlines are found to get more clicks compared to non-solution headlines. The rigor of the reporting improves product quality.

Editors who want to bring solutions journalism to their newsrooms should start with a simple question: “Is there a solutions angle to this story? As in all good journalism, new questions will follow.The reporter will not only explore the causes of a problem but ask how did people, institutions, and governments respond. Did these solutions work, and are they sustainable? In interviews, reporters should encourage subjects to talk more about constructive solutions on a personal level. What did the subjects learn, and what would they do differently? What’s missing from the public conversation?.

Which media outlets are practicing solutions journalism?

A solutions timeline

- In 1988, journalism critics in the United States questioned the quality of media coverage of the U.S. presidential election. The terms “civic journalism” and “public journalism” gain currency.

- In a 1989 speech to the Associated Press Managing Editors, NYU professor Jay Rosen called on newsrooms to “nourish public life.” The Pew Charitable Trusts starts to support civic journalism.

- In 1994, the Akron Beacon Journal won the Pulitzer Prize in Public Service for reporting on the racial divide in its community and its subsequent request for readers to help solve the problem.

- In 1996, the first issue of YES! A Journal of Positive Futures came out of Bainbridge Island, near Seattle.

- In 2003, the French NGO Reporters d’Espoirs (“Reporters of Hope”) was created by journalists and media professionals who wanted to promote solutions-based news.

- In 2006, the Canadian online news site The Tyee created a solutions fellowship to fund constructive reporting projects.

- In 2007 Lisbeth Knudsen, the editor-in-chief and CEO of the Danish media corporation Berlingske Media, called for more constructive news, in an editorial on the detrimental effects of journalism’s negativity bias. The Danish broadcaster TV2 News later launched a nightly news segment, “Yes, We Can.”

- In 2010, the journal Solutions was launched. The non-profit print and online publication showcased ideas for solving the world’s ecological, social, and economic problems.

- In 2013, the Solutions Journalism Network was founded by David Bornstein, Courtney E. Martin, and Tina Rosenberg.

- In 2015, the SJN released a downloadable “Solutions Journalism Toolkit” intended to help educate journalists interested in emphasizing solutions in their work.

- In 2017 the Constructive institute was founded.

Key quotes

Solutions journalism doesn’t spurn traditional watchdog reporting—it proposes to turn the watchdog lens on "what’s missing in today’s news: how people are responding to problems."

Why is this important?

By offering rigorous reporting on responses to social problems, solutions journalism helps societies, as it heightens accountability, strengthens audience engagement, and rebuilds trust.Killer links

- Nieman Reports Is Solutions Journalism the Solution?

- World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers Constructive News: The next mega-trend in journalism?

- Nieman Lab News got you down? Solutions-oriented journalism might be one way to re-engage local communities

- Solutions Journalism Network 17 Databases You Can Use in Your Solutions Reporting

People to follow

-

David Bornstein contributes the New York Times' “Fixes” column and are co-founders of the Solutions Journalism Network.

David Bornstein contributes the New York Times' “Fixes” column and are co-founders of the Solutions Journalism Network. -

Ulrik Haagerup is the founder and director of the Constructive Institute in Denmark.

Ulrik Haagerup is the founder and director of the Constructive Institute in Denmark. -

Cathrine Gyldensted is a constructive journalism pioneer who co-founded Open Eyes, a journalism institute in Amsterdam.

Cathrine Gyldensted is a constructive journalism pioneer who co-founded Open Eyes, a journalism institute in Amsterdam. -

Seán Dagan Wood is the publisher of Positive News, the print and online magazine that showcases positive and constructive journalism.

Seán Dagan Wood is the publisher of Positive News, the print and online magazine that showcases positive and constructive journalism. -

Emily Kasriel is head of editorial partnerships and special projects at the BBC World Service. She leads its solutions-focused journalism group.

Emily Kasriel is head of editorial partnerships and special projects at the BBC World Service. She leads its solutions-focused journalism group. -

Karen McIntyre is a constructive journalism researcher and professor at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Karen McIntyre is a constructive journalism researcher and professor at Virginia Commonwealth University. -

Michelle Gielan a former CBS News anchor, is an advocate of transformational journalism.

Michelle Gielan a former CBS News anchor, is an advocate of transformational journalism.